Women on Ekofisk

Ekofisk was the first commercial petroleum discovery on the Norwegian continental shelf (NCS). Found in 1969, it came on stream as early as 1971.

This area lies at the southern end of Norway’s North Sea sector, about 280 kilometres south-west of Stavanger, and has been developed with a central complex and several satellite fields.

arbeidsliv, kulturmøter, sikkerhetskultur

arbeidsliv, kulturmøter, sikkerhetskulturWorking on Ekofisk has always been and remains very unlike a job on land. The most eye-catching difference is the need to fly. A helicopter flight takes 90-120 minutes, depending on weather.

While at work, personnel are completely divorced from life on land and experience a total physical separation from “normal” society.

People on Ekofisk are part of a small but complex community where platform operation is the common denominator. Most workers do fixed tours of duty – usually two weeks on and three-four off.

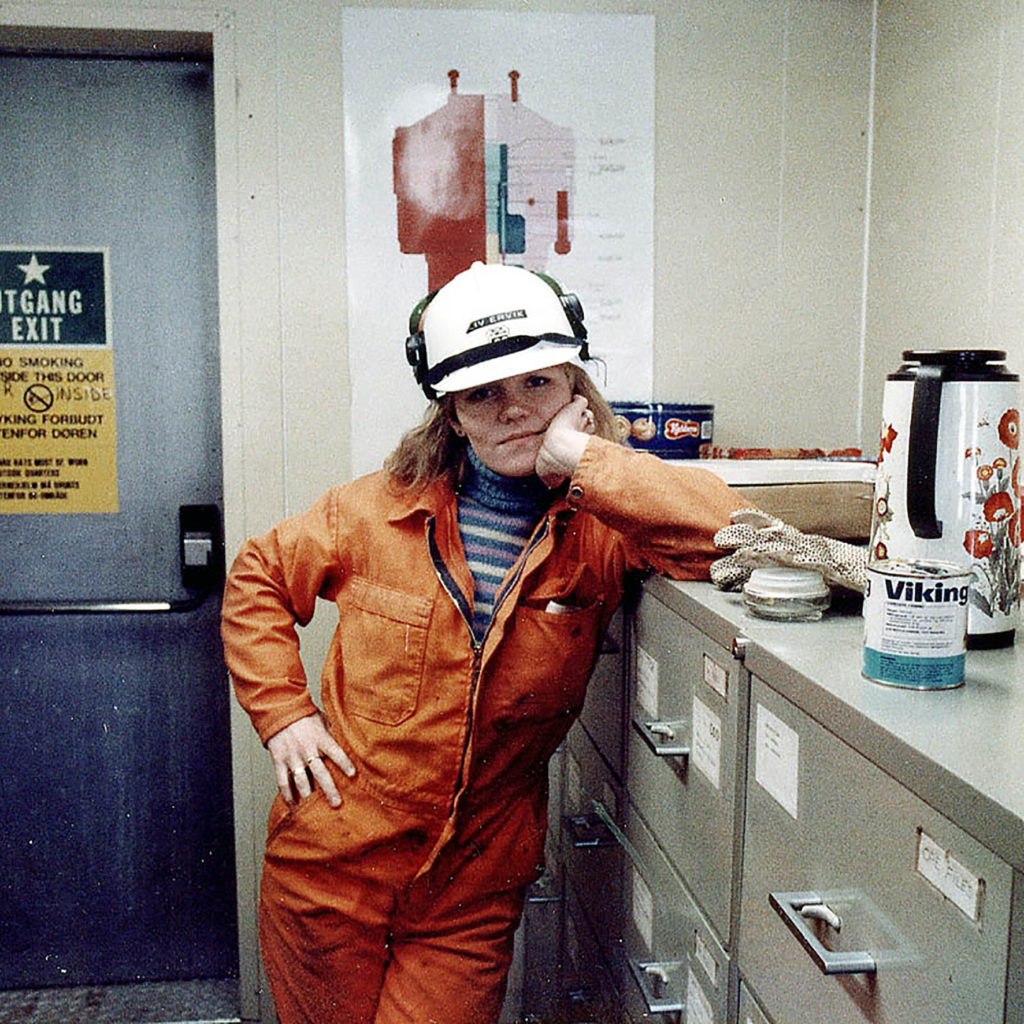

Offshore jobs were originally held exclusively by men. The first women only arrived in 1978, either as nurses or as catering personnel.

But Ekofisk remains a male-dominated arena, where women are in a clear minority at less than 10 per cent of the workforce. Catering has the largest proportion of females – just under 50 per cent. The share is significantly below 10 per cent in production and operation.

Male and female jobs

Although the bulk of the women now on Ekofisk still have jobs in the service sector, they are represented across all occupational sectors – platform management, drilling, production and operation.

The various types of work differ in their standing and prestige among those employed on the field and in the rest of society.

Social anthropologist Jorun Solheim believes that every kind of work has a gender dimension.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Solheim, Jorun and Ellingsæter, Anne Lise, Den usynlige hånd. Kjønnsmakt og moderne arbeidsliv, 2003, Oslo. By this, she means that society has generalised perceptions of “male” and “female” jobs.

A male job often relates to base or core functions in a workplace, with direct participation in what is being produced, while female work is defined as social and hygienic.

This means that a woman working in base functions on a platform, such as production, holds a “male” position and is perceived in terms of her job rather than her gender.

She is therefore judged differently from women engaged in more typically female work. So women in “male” jobs acquire a different standing both among her colleagues and in society at large from female workers in service trades. A women employed in the core area of a company works alongside men and is accepted by them. Solheim puts it this way:

The central issue is how the work itself is ‘genderised’. Particular work assignments and areas of expertise will be viewed as male or female respectively.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Solheim, Jorun and Ellingsæter, Anne Lise, Den usynlige hånd. Kjønnsmakt og moderne arbeidsliv, Oslo, 2003.

In other words, the job has a gender dimension. The individual worker is defined by the work he or she does – by whether it has a male or female character – and not by their actual gender. A man’s job has more standing and prestige than a woman’s.

So the question is whether the job done by a woman on Ekofisk determines how she is assessed, or whether gender in itself is decisive for how she is regarded and her place in the hierarchy. How are these women viewed by their female and male colleagues?

Job standing and perception of women

kvinne,

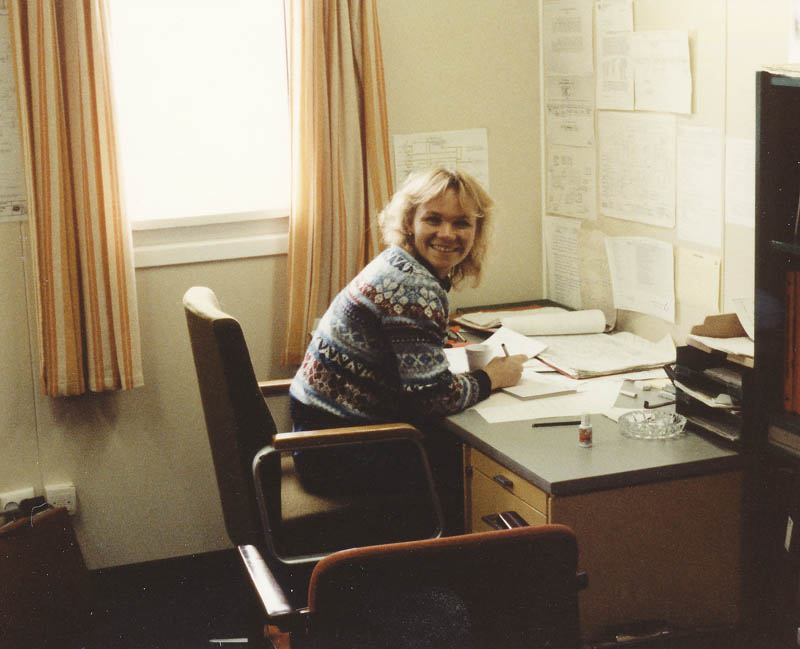

kvinne,As mentioned above, most people on Ekofisk work defined tours – two weeks offshore and three-four weeks at home. But differences exist. Working conditions and tour arrangements vary between operator employees and contractor/service company personnel.

Those employed by the operator – in this case ConocoPhillips, formerly Phillips Petroleum Company – have the most stable jobs. Their tours are fixed and they travel offshore with the same people every time.

Service company employees, on the other hand, will complete an assignment on one platform and then move to a different facility. So they will not be on the same installation for a long period.

Their position is also to some extent unstable. The duration of their work depends on a specific contract between operator and contractor. This may run over several years and can either be extended on expiry or transferred to another contractor with new personnel and rules.

Whether they are operator or contractor personnel can influence people’s view of the work and not least the employee’s own perception of their job and the associated social life. The point here is that operator employees are considered to have the most important jobs offshore and can thereby feel themselves to be superior to others.

kvinnene på ekofisk,

kvinnene på ekofisk,Education represents another important factor in the way a worker is regarded. Those with the highest qualifications often have the same educational attainment as their own managers, and thereby hold a kind of intermediate position between colleagues offshore and the land organisation.

Women in jobs which call for a high level of education avoid having to “compete” with the men in an arena where females have traditionally done less well because they lack male strength.

People with higher education and offshore experience are also qualified for a range of positions in the company, from production engineer to the partner relations department, for example. In other words, advanced technical qualifications, work in the core areas and permanent employment with the operator confer more standing than an unskilled temporary position or a job with a contractor/service company.

A skilled female technician employed by the operator has a position which awards prestige. She works in her employer’s core area and is a permanently employee.

Offshore nurses have a professional qualification and often additional training in a specialist field. They are highly educated and permanently employed by the operator. And, even though the same job on land is perceived as a female occupation, it has traditionally been a male preserve offshore.

That could partly reflect an inheritance from shipping. The first mate on a ship – a man – is often responsible for dealing with injuries. This means that the nursing function offshore has been redefined from a caring role to an expertise-based position and enjoys high standing. On the other hand, a women employed in drilling does not work for the operator but for a service company. In theory, that should indicate the job is less prestigious.

But drilling falls within the platform’s core area – no wells, no production. These workers make “first contact” with the oil or gas before it is tamed. A drilling job has a mythic quality, since it involves a certain level of risk, a level of expertise and a portion of good luck. This has traditionally been regarded as a job for the tough “lads”, and a woman who succeeds in this environment enjoys great respect. Even if she is employed by a service company, she will have high standing because of its “manly” character.

As contractors, the catering companies cover two occupational groups – the skilled cook and the unskilled cleaner. The latter has a service job traditionally associated with women, which has a female character in itself. Many cleaning personnel begin as temporary replacements before securing permanent employment, and few opportunities are available for career advancement. The work done is taken for granted and is not noticed until it has not been carried out. This provides an example of a job which confers low standing.

Spatial relationships

The platform’s spatial organisation works differently for women and men. Since the offshore environment is male dominated, arenas will exist where just men are present. But women-only places are seldom found.

Females are more or less always in mixed company and in a minority. A women thereby has few or no locations on a platform where she can simply be herself, without playing a part.

arbeidsliv, forpleining, kninne, kvinnearbeidsplass, Forpleiningstjenesten

arbeidsliv, forpleining, kninne, kvinnearbeidsplass, ForpleiningstjenestenSocial anthropologist Erving Goffman talks about people’s need for a “backstage” area. He divides social life into this and “frontstage”, or between private and public spheres.REMOVE]Fotnote: Goffman, Erving; Vårt rollespill til daglig: en studie i hverdagslivets dramatikk. Oslo 1992.

When backstage, no demands about behaviour are made and people can relax more. Frontstage is a place where they must think through and prepare their performance.

So men do not have to reflect how they appear to women when only males are present. Using Goffman’s terms, we can say that women have few backstage areas and men have more of them. This means that females must be more conscious of their performance for more of the time they spend offshore than is necessary for males.

Process engineers and nurses are examples of solo players. They will not “make a botch” of the way men in corresponding roles and at other times have done the job.

Authority

Women often lack the natural authority men possess, but can compensate for this by utilising spatial relationships to legitimise their organisational status.

An example of such conscious use of these conditions is the female offshore installation manager (OIM) who deliberately occupies the manager’s chair because those who enter her office are used to connecting it with the OIM. She wants to be associated with this role and uses spatial relationships to emphasise this.

Even though women do not control the physical or social space directly, they nevertheless exert an influence on how space is allocated and utilised.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ardener, Shirley Ground Rules and Social Maps for Women: An Introduction. Women and space : ground rules and social Oxford 1993

According to both oral and written sources, sales of after-shave in platform shops increased dramatically when women began working offshore.

Women have also exerted some influence on the design and utilisation of tools and other equipment. The Karmøy winch was developed because a female operator maintained that it must be possible to get equipment which made it easier to open valves.

Wall decoration, also part of the spatial dimension, is another area influenced by the women. After they started working offshore, fewer picture of more or less semi-naked models have adorned work spaces and offices.

Social relations

Arbeidsliv, Organisasjon og yrker, Yrkesgrupper offshore, Sikkerhetsavdeling, helsetjeneste

Arbeidsliv, Organisasjon og yrker, Yrkesgrupper offshore, Sikkerhetsavdeling, helsetjenesteA platform is much more than a workplace. By extension, it is also a small but complex community on an artificial island where people live 24 hours a day.

This society is characterised by the need to perform many different functions and, in order to achieve that, people need to specialise.

Like the wider society on land, the Ekofisk community is complex because a great variety of activities have to be pursued. Some people are specialists on process, others on drilling or mud.

A complex society is also characterised by the fact that only partial identities are expressed through interactions in the various settings.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Solheim, Jorun and Ellingsæter, Anne Lise, Den usynlige hånd. Kjønnsmakt og moderne arbeidsliv, 2003, Oslo.

The expression “partial identities” means that people do not see the whole person in their job, but only that part which is “relevant” to what they are doing there.

Nevertheless, the fact that personnel live on a platform around the clock will allow more aspects of their personality to emerge.

Occupational identity is central, largely fixed – and not negotiable. What can be negotiated or personally determined is whether the time offshore will be positive, whether one is going to be social.

People put each other in social categories and simplify by creating stereotypes. Anthropologist Gregory Bateson sees this need for simplification as a result of information overload which requires us to bring things down to a more manageable level.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Solheim, Jorun and Ellingsæter, Anne Lise, Den usynlige hånd. Kjønnsmakt og moderne arbeidsliv, 2003, Oslo.

Statements such as “women in aspirational jobs … aren’t here long” about university-trained engineers reflect a stereotype of a feature or property of females with such qualifications.

It is easier to avoid leisure contacts with work colleagues on larger platforms. You can expect “somebody else” to be engaging in social interaction, so your absence will not be noticed.

Pressure to be sociable can be stronger on smaller installations, and you will feel under a greater obligation to be present in common parts.

It is particularly difficult for women to evade social relationships on a small platform because there are so few of them that their absence will be immediately noticed.

Job affiliation

Different levels of affiliation to the job appear to affect how a person integrates with the platform community. Those permanently employed offshore and in stable jobs – whether for the operator or a contractor on a long-term contract – are more assimilated.

This group includes personnel in both production and service roles – process operators, nurses, radio operators, administrators and catering employees. They are often well integrated in the platform community and also have friends among those they have met offshore.

The exception is the nurses. Even though they are well assimilated, a number of female medical personnel indicate that they avoid over-close relationships for professional reasons.

Highly educated technical personnel and service company employees are often less integrated because their jobs are not permanent.

The same seems to apply to managers in typical career posts. It appears that the higher up the hierarchy a person is, the more formal their relationships will be.

With the role structure more strictly defined, such people are required to behave more formally. Formal structures create clear divisions of roles and demands for bodily control.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Douglas, Mary; Natural Symbols : explorations in cosmology. London 1996.

A woman in a management position offshore seldom has female colleagues at the same level. Should the job also absorb most of her time, it is hard to become intimate with other women.

If they are at work the whole time, social interaction becomes part of the job and the boundaries between work and leisure get blurred. That applies primarily to nurses and OIMs, who are always on call.

Everything was better before

Those who have worked offshore for a long time have claimed that everything was nicer before. Typical comments include: “we were all more united then”, “there’s much more division now”, and “we had a much better time”.

The reason why earlier times were finer was that certain jobs had fewer responsibilities than today. And TV sets in cabins with masses of channels must take a share of the blame for people being less sociable.

Leisure activities

Various leisure activities are available offshore. These normalise the time spent there, and help to break up the routine of work, eat and sleep.

They help to make the time more meaningful. When a job is characterised by routine, a hobby which allows people to express their creativity can aid relaxation.

Male-female relations

Everyone believes that having both genders represented on the platforms is beneficial, even though some people were sceptical to begin with.

Where women work in relation to the men has an impact on their bonding. Those who interact closely with male colleagues usually have man-to-man types of association – friendship, collegial ties, a superior-subordinate relationship and so forth.

Most emphasise the importance of not ending up in woman-man ties, such as becoming sweethearts or lovers, because this undermines the respect they have built up at work.

Gender is toned down. The great majority of women are keen to play down their female attributes.

Loose-fitting clothes and no makeup are standard for many of them offshore – regardless of the type of job they have.

But women in catering do not have the same need to play down their femininity. Because they work in “typical” female occupations, others accept if they act as women.

Women in other roles find it advantageous that somebody else serves as the centre of male attention. Job affiliation appears to be crucial in determining which females are possible objects for chatting up. Those working in catering are considered “worth trying it on with”, while a woman who is seen as one of the “lads” is not perceived as female in the same way.

Female morality debated

Romantic relationships have arisen in the North Sea, as in other workplaces. Some have led to lasting partnerships, while other love affairs have been more transitory.

Informants make such observations as “she was a lady of the more generous type and keen on men”, or “there were some who went right off the rails from all the attention”.

Most of the stories about these transitory romances are characterised by the fact that the discussion concentrates on the woman’s behaviour.

This represents a nature-culture dichotomy, where men are regarded as closer to the culture while women are closer to nature, because female morality becomes the point at issue.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ortner, Sherry; ed. Rosaldo, Michelle Zimbalist and Lamphere, Louise; Is Female to Male as Nature is to Culture? Woman, culture, and society Stanford University Press, 1974.

The woman is the one who steps outside the accepted norms, and who can undermine the position of other females by giving their whole gender the stamp of immorality.

Women are felt to have only themselves to blame if they are not properly treated offshore. In other words, a woman who is subject to verbal or other harassment has given the wrong signals and brought it on herself.

Catering workers are often regarded as group which represent a social factor by definition. First, most of the females on a platform are found here, and part of their job is to create homelike conditions for the others.

These personnel are metaphorically the “mothers” in the big platform family..[REMOVE]Fotnote: Solheim, J, og Hanssen-Bauer, J. Kompleksitet og fellesskap på en Nordsjø-plattform : rapport fra et besøk på Statfjordfeltet Rapport / Arbeidsforskningsinstituttene, Arbeidspsykologisk institutt, Prosjektgruppe Arbeidsmiljø på kontinentalsokkelen ; 108/83 Oslo : Arbeidsforskningsinstituttene, Arbeidspsykologisk institutt. They are the ones who create the “domestic” environment with good food and clean, tidy rooms. At the same time, they come into contact with many other occupational groups offshore.

Women in this occupation can allow themselves to categorise males by different criteria than those used by females who work closely with men because they see what lies behind the male facade. Catering gets closer to the private sphere of the other personnel.

Must fit in

Virtually all women employed offshore find it positive to be working in an environment with many men. The attitude is that “if you’re straightforward and genuine yourself, you get a lot back” and “you learn what men are like when you work in a male society”.

The woman is the one who must cope with being in a masculine workplace. “It’s good to have more females, but you must fit it,” is a frequent comment. That refers to succeeding not only in working so intensively, but also in being a woman in a relatively marginal position.

Social relations on land

arbeidsliv, sosialt liv, fritid, telefonkiosk,

arbeidsliv, sosialt liv, fritid, telefonkiosk,A factor which is not visible offshore but very definitely present is the relationship with family and friends on land. Most of the women in this study have both husband and children.

Many were mothers when they started working offshore, or have since become so, and have had one or two periods of maternity leave.

Combining a platform job with family life on land is not regarded by the informants as particularly problematic. On the contrary, they have organised themselves in such a way that working offshore and having a good time when at home is preferable to a nine-to-five job ashore.

Some of the mothers have been single parents or shared care with the child’s father. Many have a good network of friends and family who help out when they are offshore. In many cases, it is society at large which makes a problem out of a mother being away from their offspring.

Responsibility for organising matters at home appears to rest with the women. Earlier studies of male offshore workers and feedback from such informants indicate that men employed offshore fail to accept the same level of responsibility for their family.

The helicopter flight from/to land is a key part of working offshore. This journey has been called a rite of passage, but many experience their whole time on the platforms as a marginal phase. You travel from something, spend time away from “normal” society, and reintegrate with it when your tour is over.

A number of North Sea workers start their offshore tour well ahead of flying out. The transition from normal life on land to one directed at their platform job occurs before they depart.

That applies primarily to women. Many of them plan the life of their family while they are away. They organise, clear up and put things in order to minimise the drawbacks for those staying at home. Men are more “a soul and a shirt” when they set off.

Being visible

Everyone positions themselves and has their standpoint, including those who regard women from the outside and communicate their view. Media want to talk about the North Sea pioneers, labour disputes and special episodes.

The various magazines published by companies say something about their corporate identity: “We support women offshore, and give them opportunities, we want to come across as a company where equal opportunities are important”.

While the positive woman is presented in personal in-depth interviews, however, the negative ones get presented as a group. Females are stigmatised as grumblers and malcontents.

The women worth presenting are the distinctive individuals who become the first to hold a particular job, usually a high-status post previously reserved for men.

Different jobs carry varying weight when describing them. Stories about a hard grind in a tough masculine occupation get more attention than ones on drudgery in the physical care sectors.

Being visible can also be interpreted as others seeing what you do. Many offshore workers find that they are regarded as people who make good money and have a lot of free time – who are better off than others.

Å bli sett kan også tolkes som det at andre ser hva man gjør. Mange som jobber i Nordsjøen erfarer at de blir sett på som personer som tjener godt og har mye fri. De blir sett som folk som har det bedre enn andre.

Neighbours and friends have no idea what happens out in the North Sea, and women working offshore find little understanding in their home environment of what their job is like.