Safety on Ekofisk – and on the NCS

Oil and gas operations on the Norwegian continental shelf (NCS) are perpetually changing, with knowledge and technology making constant progress. New ways of operating get introduced, and digitalisation has demanded major organisational changes in recent times. HSE must adapt to a changing reality. Safety is a perishable commodity, and must always be high on the agenda. “Good enough” is not sufficient, either for the Norwegian government or for ConocoPhillips.

The goal of being best in the world – and in Norway – calls for continuous safety improvements. That requires good interaction between human, technological and organisational (HTO) factors.

Procedures and technical safety will always provide the bedrock in this endeavour. But the concept of corporate culture also became a key part of the safety mindset in the 1980s. A number of behavioural and cultural programmes have been adopted – along with new ways of thinking about safety. Some of the priority areas are covered below.

Understanding how and why these innovative approaches came to characterise safety on the NCS and Ekofisk needs to start with a review of relevant historical developments off Norway.

Workers heard

The first and biggest change in offshore safety came with the Norwegian Working Environment Act of 1977, which was extended to fixed installations on the NCS the following year.

This legislation was aimed at protecting job conditions, ensuring equal treatment at work and securing collaboration between employer and employees. It involved a sharp upgrading in employment rights compared with the Worker Protection Act of 1956. Elected safety delegates and a working environment committee became mandatory in companies, while worker participation in decision-making was given legal force.

Starting from an acknowledgement that people make mistakes, the Act specifies that safety work in companies must therefore aim to reduce the consequences of such human errors. Working conditions and technology must be tailored to the employees – the goal of safety efforts is not to change people but the conditions they work in.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Foss, G (2006). Adferdsbasert Sikkerhet i En Norsk Kontekst: Petroleumsnæringen Som Case, 2006. MSc thesis, faculty of social sciences, University of Stavanger: 21.

Democratically elected by the workforce, safety delegates were given greater rights to intervene in work processes. That included the power to halt dangerous work, which represented a substantial constraint on the employer’s right to manage.

Rooted in the Working Environment Act, the safety regime for the petroleum industry continued to develop on the basis of the “Norwegian model”. This social template comprises a strong welfare state, a regulated labour market and an interventionist collaboration between three parties – employers, unions and government. Where the oil and gas sector are concerned, the model involves government – represented by ministries and regulators – companies and unions joining forces to develop pay and working conditions, including HSE.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Meland, T (2016), “Sikkerheten utfordres”, Norsk Oljemuseums årbok 2017: 43.This tripartite collaboration involves a principle of equality and depends on trust, good communication and mutual recognition of roles and responsibilities.

However, this trust and mutual recognition have been challenged at times – particularly when the Norwegian economy has taken a turn for the worse.

Phillips Petroleum was an early adopter of the safety delegate system. It introduced this on its Ekofisk platforms in 1976, two years before the Act came into force offshore. That was not only to be proactive, but also because the Ministry of Industry ordered this following a fire on Ekofisk 2/4 A where three people died.[REMOVE]Fotnote: The ministry ordered Phillips on 4 December 1975 to establish a safety delegate service covering contractors and sub-contractors involved on the field. See Smith-Solbakken, Marie, and Vinnem, Jan Erik “Alfa-plattform-ulykken”, Store norsk leksikon, 18 November 2019.An industrial safety and environmental committee was also appointed, which became a forerunner of the mandatory working environment committee required by the Act. Read more: Fire om Ekofisk 2/4 A

Self-regulation and collaboration

In the early phase on the NCS, during the 1970s, offshore safety was largely dealt with through extensive regulations, checks, inspections and detailed orders. This regulatory approach was difficult to administer and supervise, and the constant introduction of new technology demanded continuous updating of the rules. Such detailed control also undermined the industry’s understanding of its own responsibility as well as hampering innovation and creativity.

In order to develop a more flexible system and give the players a greater sense of responsibility, a form of self-regulation was gradually applied to the companies in the 1980s. This involved a shift from specific regulatory demands to performance-based requirements – detailing what standards were to be attained, but not how that was to be done. The companies were given growing freedom to choose what safety solutions they wanted to apply, and greater opportunities to blend technology, experience and creativity in cost-effective ways. A precondition for such performance-based regulations was the tripartite collaboration mentioned above, with its mutual trust between employers, unions and government.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Foss, G (2006). Adferdsbasert Sikkerhet I En Norsk Kontekst: Petroleumsnæringen Som Case, 2006. MSc thesis, faculty of social sciences, University of Stavanger: 24.

Establishing formal interaction between the parties took time, but an external reference group for regulations was set up in 1986. Chaired by the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate (NPD), this forum included unions and employer organisations in the oil and gas sector as well as government authorities. That arena made it possible for members to keep abreast of ongoing regulatory work and to comment on important proposals as they were made. In turn, this created greater ownership of, and consensus on, the final proposals.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Report no 7 (2001-2002) to the Storting, Om helse, miljø og sikkerhet i petroleumsvirksomheten, Vol no 7 (2001-2002), Ministry of Labour and Government Administration, Oslo, 2002: downloaded from https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/stmeld-nr-7-2001-2002-/id134387/sec2.

Continuous safety improvements became the motto, with operations on the NCS becoming steadily safer in the 1980s. They eventually set a standard for other industries exposed to risk.

More conflict

During the 1990s, mutual trust between the parties in the Norwegian petroleum sector gradually weakened and the level of industrial conflict increased.

The conditions which had underpinned the safety system in the 1980s changed as the industry experienced rapid technological progress and constant reorganisations.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Alteren, B, and HSE Petroleum: “Endring – organisasjon – teknologi”, HMS-arbeid under endring, 2003 (topic 4 in HSE Petroleum K2: Endring, organisasjon, teknologi). Vol STF38 A03406, department for safety and reliability, Sintef (printed edition). Sintef, Teknologiledelse, sikkerhet og pålitelighet, Trondheim: 11.

Oil prices were also substantially lower for most of the 1990s than they had been in the previous decade, and a big slump began in 1998 – with a corresponding decline in profitability. In cooperation with the authorities, the industry initiated a far-reaching campaign to reduce costs. This led not least to restructuring and downsizing. Meanwhile, the unions had been weakened by a number of tough labour disputes as well as mutual rivalry and internal disputes. Read more: From in-house association to independent union.

The level of safety and risk on the NCS was nevertheless regarded as good. Improvements were admittedly no longer seen, but both companies and government felt that conditions had stabilised at a high level.

So the NPD’s injury statistics, which were based on lost-time injuries (when the victim was unable to work after an accident), showed no deterioration. But those working offshore were constantly voicing concerns. Although accidents and lost-time injuries had not risen, a number of serious incidents were occurring on the NCS. These included big gas leaks, well kicks and collisions between units.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Report no 7 (2001-2002) to the Storting, Om helse, miljø og sikkerhet i petroleumsvirksomheten, Vol no 7 (2001-2002), Ministry of Labour and Government Administration, Oslo, 2002: downloaded from https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/stmeld-nr-7-2001-2002-/id134387/sec2. Several unions expressed worries about the increased risk of major accidents.

However, the oil companies did not accept this negative picture. They reported that, despite several serious incidents, safety had never been better.

Certain top executives even claimed that safety attracted too much attention and absorbed excessive resources. Union concerns were considered by some to be camouflage for underlying social and economic motives.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Ryggvik, Helge, R (2004). Fra forvitring til ny giv: Om en storulykke som aldri inntraff? Working note no 26: 13.

So how could two such different perceptions of reality exist side-by-side? The answer may lie in the lack of suitable measurement tools for risk assessment.

The NPD had to acknowledge that a mismatch existed between the number of incidents offshore and in the injury statistics, and that available tools gave an inadequate basis for establishing the true level of risk on the NCS. It took the initiative to develop a new approach to measurement in this area, which became a study entitled “trends in risk level on the NCS” or RNNS.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Now “trends in risk level in the petroleum activity” (RNNP). The project was unique in that it combined quantitative data with qualitative observations and analyses. Work on it got going seriously in the winter of 2000.

From an early stage, it became clear that the indicators produced by the RNNS revealed a worrying trend. This challenged the tripartite collaboration, and undermined the mutual trust underpinning the whole safety system. “We’re registering far too many serious incidents out on the platforms,” Magne Ognedal, the NPD’s safety director, told Oslo daily Dagbladet. “I don’t have a good gut feeling any more.”[REMOVE]Fotnote: Stang, Leif, 16 October 2000, “Frykter storulykke”, Dagbladet. He and his boss, NPD director general Gunnar Berge, sent a joint letter to the industry ordering it to take “new” steps to reduce the level of risk. This must be seen as a sharp reprimand to the whole sector.

Ekofisk difficulties

The general level of safety improved on the NCS in 1980s, but the conditions which caused the subsequent weakening also applied to Ekofisk and Phillips. Like most of the oil companies, the latter cut back its workforce sharply in the late 1990s.

At the same time, the Ekofisk Committee – the biggest union on the field – had been weakened by internal disputes. It had left the Federation of Offshore Workers Trade Unions (OFS) and joined the Norwegian Oil and Petrochemical Workers Union, part of the Norwegian Confederation of Trade Unions (LO). See article: Ekofisk Committee merges with NOPEF.

Undesirable incidents, such as suspended loads being dropped, chemicals escaping to the sea and gas leaks, were also reported in the Greater Ekofisk Area. See the separate articles: Fatal work accident, Chemical spill to the sea, Seabed gas leak halted, Shut down by gas cooler leak.

Political reactions

In parallel with the adoption of the RNNP tool, the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy produced Report no 39 (1999-2000) to the Storting (parliament) on 9 June 2000. This White Paper declared that oil and gas operations were being pursued within a prudent framework, but also noted the NPD’s assessment that the overall level of risk was increasing.

At the same time, the NPD had found that virtually all accidents and injuries could ultimately have been avoided.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Report no 7 (2001-2002) to the Storting, Om helse, miljø og sikkerhet i petroleumsvirksomheten, Vol no 7 (2001-2002), Ministry of Labour and Government Administration,Oslo, 2002: downloaded from https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/stmeld-nr-7-2001-2002-/id134387/sec2: 107. It felt that the most important improvement potential related to workplace customisation and making individual workers more aware.

Eighteen months after the petroleum ministry’s White Paper, in December 2001, the Ministry of Labour and Government Administration presented Report no 7 (2001-2002) to the Storting.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Constitutional responsibility for safety and the working environment in the petroleum industry had been transferred to the Ministry of Local Government and Labour, later the Ministry of Labour and Government Administration.This criticised the way the companies organised safety, and particularly the failure to give sufficient emphasis to tripartite collaboration and worker participation. The companies were ordered to maintain their commitment to technology development which aimed to achieve improvements in the HSE area.

A new concept was introduced by the White Paper – the zero mindset. This reflects the view that accidents do not happen, but are caused. All can therefore be prevented. The goal was to be zero injuries and accidents, which required establishing accountability at every level and paying continuous attention to risk management, prevention and learning lessons.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Report no 7 (2001-2002) to the Storting, Om helse, miljø og sikkerhet i petroleumsvirksomheten, Vol no 7 (2001-2002), Ministry of Labour and Government Administration,Oslo, 2002: downloaded from https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/stmeld-nr-7-2001-2002-/id134387/sec2. This can be interpreted as an assumption by the government that human behaviour was the underlying cause of accidents and injuries.

But the zero mindset was only a small part of the White Paper, with the ministry giving the main emphasis to accountability and concentrating on risk management, prevention and learning lessons.

The NPD followed up by fronting risk management and improvements to safety technology which could reduce risk – along with a good safety culture.

Managing safety at work would remain entrenched in legislation, regulations, guidelines and standards. The actual management job was governed by the internal control regulations, which addressed systematic HSE work by companies. Barrier thinking became an important condition for good safety and risk management. According to the Petroleum Safety Authority Norway (PSA),[REMOVE]Fotnote: The NPD was split in 2002 into two independent agencies, with that part of the directorate which had dealt with safety and the working environment becoming the PSA with effect from 1 January 2004. It reported to the Ministry of Labour and Government Administration. its purpose is “to establish and maintain barriers so that the risk faced at any given time can be handled by preventing an undesirable incident from occurring or by limiting the consequences should such an incident occur”. Normal practice is to divide barriers into three main types – organisational, technical and human/operational – although these can be difficult to distinguish from each other. However, organisational barriers include procedures, specifications, work permits, management systems and safe job analyses (SJAs). The human barriers, for their part, involve knowledge, experience, characteristics and behavioural patterns. While technical barriers can in principle perform their function on their own, they should and must often be combined with organisational and/or operational components. But people and organisation cannot serve as a barrier function on their own. They must always be combined with at least one of the other types.

Barrier thinking is closely related to high fault tolerance – which means that a system continues to function if something goes wrong. Inbuilt capabilities limit the consequences of such faults.

Another important safety-related concept is redundancy, which involves an additional margin being built into systems where a high level of reliability is essential. A cornerstone of modern safety thinking, redundancy refers to the degree of reserve capacity – technical or human – in a system or an organisation.

How this affected Ekofisk

After 2000, the behavioural aspect was given ever-increasing emphasis in safety work as the zero mindset spread rapidly through the Norwegian oil industry. This conveys a simple message which is difficult to disagree with, setting a long-term goal of preventing harm to people and the environment and of avoiding accidents and losses. ConocoPhillips was one of the many companies to embrace the zero mindset, and it formulated its safety goal from 2003 as “zero undesirable incidents”.[REMOVE]Fotnote: “Målet er null uønskede hendelser”, Pioner, February 2003.

The following appears on the company’s website: “More than ever, the company will promote a culture that focuses on safety in everything we do, by implementing the zero philosophy to eliminate unintentional incidents. “The zero philosophy is intended to reduce the number of injuries and critical incidents to zero. Attitudes are a key element of our safety training to ensure that everyone takes responsibility for their own and co-workers’ safety.”[REMOVE]Fotnote: http://www.conocophillips.no/social-responsibility/health-safety-and-environment/.

Human behaviour acquired an important role in the zero mindset, and ConocoPhillips worked on the principle that changing the way employees thought and acted would improve safety. As the company itself expresses this: “recognise that harm does not occur – it is created – and that it is the individual’s attitudes and experience which help to avoid harm”.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Stolpe, M (2007). Nullfilosofi i Praksis: Et Case Av Statoil Mongstad, IV, 139: 48.

Under the slogan “Our safety, my responsibility”, a number of different awareness-raising measures and attitude-changing campaigns were initiated.

Four Rs

It would not be true to say that the zero mindset and the concentration on human factors as safety risks were introduced to Norway’s oil sector by the 2001 White Paper. Behavioural or cultural programmes directed at changing employee behaviour and attitudes were a trend which had already been heading towards the NCS for several years.

As early as 1996, Phillips introduced its 4R programme, which aimed to create a workplace free of accidents and serious incidents. Its title stood for register, report, react and reduce.

Like most other companies, Phillips believed that existing systems and procedures took care of the risk that a major accident might occur.[REMOVE]Fotnote: “4R er godt i gang”, EkofiskNytt, no 21, week 50, 1996.

The 4R programme aimed to register and report all types of incidents in the workplace, including poor behaviour and hazardous conditions as well as site untidy conditions. Every case would lead to a reaction from the company – in other words, a follow-up – in order to reduce the risk of accidents. An important consideration was that employees would become conscious of and involved with their own working habits and those of others. Such involvement would develop preventive behaviour, with employees becoming more aware of the errors they and their colleagues were making. This forms part of what is known as organisational redundancy in safety work. Employees will consult with, check and correct each other. Ekofisk personnel would “use a magnifying glass to uncover every hazard before an undesirable incident occurs”.[REMOVE]Fotnote: “Økt satsing på forebyggende sikkerhet”, EkofiskNytt, no 20, 1996.The company’s new vision was an accident-free environment at work offshore and on land, as well as in the home.[REMOVE]Fotnote: “Økt satsing på forebyggende sikkerhet”, EkofiskNytt, no 20, 1996. In other words, changes in behaviour and attitudes would not only colour life on the platform, but also ashore and domestically.

With 4R designed as a low-threshold scheme, personnel were required to note down observations in the workplace and deliver them to their immediate superior. And management was to give feedback about how the matter was dealt with. This system was a tool for getting to grips with the small issues which were not defined as an incident, but which might lead to one later if management failed to deal with them.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Bjørn Saxvik, HSE manager, Greater Ekofisk Area operations. Interviewed by Kjersti Melberg and Trude Meland, Norwegian Petroleum Museum, 16 October 2019.Implementing the programme – still in use today across the Greater Ekofisk Area – on the various platforms was ranked on a scale from one to 10. It applied initially to cleanliness and tidiness, and prizes were awarded for passing level six.[REMOVE]Fotnote: “Økt satsing på forebyggende sikkerhet”, EkofiskNytt, no 20, 1996.

Phillips and the other companies on the NCS were not alone in implementing such cultural and awareness processes. The ideas came primarily from large consultancies known for their safety systems, which developed strategies and campaigns purchased and applied by the oil companies.

The largest and best-known of these consultants was DuPont, an American chemicals group which has specialised in safety and protection. Its work was based on a theory that 85-95 per cent of all accidents were caused by human error and that a correlation existed between hazardous behaviour and major accidents. The latter are regarded as acute incidents which immediately or subsequently cause serious personal injuries and/or fatalities, serious damage to the environment and/or loss of major material assets.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Meland, T (2018). “Sikkerheten utfordres”. Årbok Norsk Oljemuseum 2017: 39.

Often called the iceberg model, the theory applied by DuPont has occupied a key place in the petroleum industry over the past 20 years and also comes in a popular version. This states that incidents, minor accidents and near misses, and major accidents all have the same causes and that the relationship between them is constant. Reducing the frequency of minor accidents will therefore produce a corresponding cut in the risk of major disasters.

Although the iceberg model is not often referred to directly in communications from ConocoPhillips, it nevertheless underlies the many campaigns pursued by the company. These ideas are controversial internally, and not everyone is equally convinced about the correlation between behaviour and major accident risk, or the value of the theory.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Bjørn Saxvik, HSE manager, Greater Ekofisk Area operations. Interviewed by Kjersti Melberg and Trude Meland, Norwegian Petroleum Museum, 16 October 2019.Nevertheless, the belief that the key to improved safety lies in changing worker behaviour is fundamental to much of the organisation in this area at ConocoPhillips.

Key conversation

The 4R programme was the first awareness campaign initiated by Phillips to improve safety through behavioural change, and was followed during the 2000s by a number of similar drives.

Phillips merged in 2002 with Conoco, another US oil and gas company which had been part of DuPont from 1981 before being sold off in 1999.

After the link-up, the renamed ConocoPhillips company launched a new personal safety involvement (PSI) awareness programme based on a template developed by Conoco and DuPont. This was also inspired by Statoil’s new “open safety conversation” awareness programme, which the Norwegian state oil company had introduced in 2002.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Bjørn Saxvik, HSE manager, Greater Ekofisk Area operations. Interviewed by Kjersti Melberg and Trude Meland, Norwegian Petroleum Museum, 16 October 2019.

PSI builds on the theory that the great majority of accidents are attributable to human action, such as unsafe behaviour and poor working habits, and aims to address such aspects anew.[REMOVE]Fotnote: “Samtaler om sikkerhet”, Pioner, June 2004.

It is based on creating the good conversation in the workplace, being present and daring to admit one’s incompetence. Through conversing, employees will learn how to talk to each other about work-related assignments and circumstances.

Training programmes, activities and lectures were developed. The formal PSI lessons comprised two-hour practice conversations for awareness training, a full-day course and a training camp where participants formulated and agreed on HSE obligations.

Before a job can start, its risk aspects and possible injury prevention measures must be discussed between the supervisor and those doing the work. This conversation is intended to function as an approach to setting targets which make safety a natural part of the workplace culture.

PSI is regarded as a management tool for eliminating risky behaviour, as in-house magazine Pioner reported in a 2014 article:

Managers, supervisors and safety personnel will visit groups and individuals in the workplace and conduct a conversation about safety measures with those doing the job. The topic of the chat is how safety has already been put into effect and how [it] might be enhanced in the relevant work operation. The manager will then fill out a simple report on the safety conversation, which is filed for further processing.[REMOVE]Fotnote: “Samtaler om sikkerhet”, Pioner, June 2004.

The falcon was chosen as a symbol, the article noted. Its sharp eye, viewing the world from great heights and swiftly closing in when it has a specific target, is the behaviour ConocoPhillips wants from its employees.[REMOVE]Fotnote: “Samtaler om sikkerhet”, Pioner, June 2004.

PSI remains the most important instrument for improving the safety culture on Ekofisk. It is important to emphasise that this was not introduced as a replacement for other safety measures, but as a supplement. Tools such as SJAs and work permits (WPs) still underpin all operations carried out offshore.

An SJA is a systematic and step-by-step review of all risk elements before starting a job or operation, in order to identify possible measures to remove or control identified hazards. For its part, a WP provides written authorisation to perform a defined job in a safe manner at an given place on a facility and under specified conditions. This will ensure that normal barriers are not removed without compensatory measures being adopted. It also ensures that all other activities on the facility are assessed to avoid unintentional consequences or undesirable incidents escalating.

A common model for WPs and SJAs has been developed for use on the NCS. While safety delegates do not have a particular role in approving WPs, they play a defined part in SJAs.

Spirit values

Operations at ConocoPhillips have eventually become entrenched in a set of values known as Spirit – for safety, people, integrity, responsibility, innovation and teamwork.

This applies not only locally in Norway but also for the group worldwide, and is intended as guidance on how work should be done across the whole organisation.

- Safety: we operate safely.

- People: we respect one another, recognising that our success depends upon the commitment, capabilities and diversity of our employees.

- Integrity: we are ethical and trustworthy in our relationships with stakeholders.

- Responsibility: we are accountable for our actions. We are a good neighbour and citizen in the communities where we operate.

- Innovation: we anticipate change and respond with creative solutions. We are agile and responsive to the changing needs of stakeholders, and embrace learning opportunities from our experience around the world.

- Teamwork: our “can do” spirit delivers top performance. We encourage collaboration, celebrate success, and build and nurture long-standing relationships.

Spirit builds on a recognition that safety is always the most important consideration. The group’s expressed goal is to have a safety culture which yields top HSE results. As part of its awareness work and compliance with the Spirit values, ConocoPhillips developed a three-point HSE policy:

- work is never so urgent or important that we cannot take the time to do it safely and in an environmentally responsible manner

- we will always set specific HSE goals for all our activities, and strive at all times for continuous improvement

- against the background of the setting in which we pursue our daily work, contributing to sustainable development is a duty and important strategy for us.[REMOVE]Fotnote: ussand, Kjetil L, and Kleggetveit, Stian K (2014), Kunnskapsoverføring – En Vei Til Økt Sikkerhet: 60.

Life-saving rules

The International Association of Oil and Gas Producers (IOGP), to which ConocoPhillips belongs, published a set of life-saving rules in 2010 aimed at reducing risk and eliminating serious incidents in the industry.

This code was not intended to address all risks and hazards in the oil and gas sector, but to call attention to activities where the threat of accidents was highest. It supported existing company systems rather than replacing their management solutions, guidelines, safety training programmes, operating procedures or work instructions.

With the life-saving rules, the IOGP has turned the spotlight on activities which have shown the greatest probability for accidents with fatal consequences.

The idea is that standardising these principles will simplify training, assist compliance with and understanding of critical precautions, and help with experience transfer.

Virtually all the operators on the NCS were quick to adopt these rules, with ConocoPhillips opting to apply eight such provisions.

These would support and strengthen existing safety programmes and contribute to reaching the HSE goal of zero undesirable incidents. The rules applied to the group’s own employees and contractors everywhere it operated, and were to be a permanent part of its corporate culture.[REMOVE]Fotnote: “Bringing safety to life”, Spirit, ConocoPhillips, 2014.

These eight are as follows:

- Work with a valid work permit when required.

- Obtain authorisation before entering a confined space.

- Protect yourself against a fall when working at height.

- Follow safe lifting operations and do not walk under a suspended load.

- Verify isolation before work begins.

- Obtain authorisation before starting ground disturbance or excavation activities.

- Obtain authorisation before bypassing, disabling or inhibiting a safety protection device or equipment.

- Wear your seat belt, obey speed limits and do not use any mobile device while driving.

A ninth life-saving rule on keeping out of the line of fire was later introduced by the IOGP. And rules on establishing and respecting barriers and exclusion zones were also incorporated in ConocoPhillips Norway’s safety culture to eliminate undesirable incidents.

New crisis – new spotlight

After many years with high oil prices, Norway and the rest of the world saw them slump sharply during 2014 – which led in turn to cost cuts and downsizing in the Norwegian petroleum sector. Concerns quickly arose that efforts to trim spending would have a negative impact on safety in the industry. Although major incidents had been avoided, the business was not accident-free. The safety position on the NCS was again characterised in 2015-16 by a number of serious occurrences and other challenges, at the same time as big change processes, reorganisations and redundancies were under way. A number of media stories suggested it was appropriate to ask whether safety on the NCS was being sacrificed in an economic downturn.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Meland, T (2016), “Sikkerheten utfordres”, Norsk Oljemuseums årbok 2017.

Journalists were not alone in posing such questions – government regulators, unions and public opinion all gave expression to concerns about the level of safety.

Against that background, Anniken Hauglie, the Conservative minister for labour and social affairs, appointed a committee to address this issue. It was charged with determining whether a connection existed between the many incidents offshore and the big cost cuts made by the industry in the wake of the 2014 oil price slump. A report was produced, and formed the basis for Report no 12 (2017-2018) to the Storting on HSE in the petroleum industry – the first White Paper on the subject in seven years.

Both this document and the preceding committee report concluded that tripartite collaboration was functioning well, but faced challenges. As a result of restructuring and efficiency improvements, company organisations were devoting less time and resources to tripartite work. But the difficulties seemed even greater for employer-employee (bipartite) relations.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Meland, T (2016), “Sikkerheten utfordres”, Norsk Oljemuseums årbok 2017.

The White Paper nevertheless concluded that Norway’s HSE regime was by and large in good shape, and that the main provisions in the regulations were robust and should be retained.

During and after this oil crisis, cutting costs was important for ConocoPhillips – as it was for all the other players in the sector. The company was robust, but had to take some action. The workforce was downsized, although without compulsory redundancies. Ensuring that the process was voluntary ensured calm in the organisation, reports Bjørn Saxvik, HSE manager for Greater Ekofisk Area operations.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Bjørn Saxvik, HSE manager, Greater Ekofisk Area operations. Interviewed by Kjersti Melberg and Trude Meland, Norwegian Petroleum Museum, 16 October 2019.

During the oil industry downturn in 2014, Steinar Våge, the regional manager in ConocoPhillips at the time, reported that the company’s positive safety trend was also going into reverse. Now was the time to sharpen up. To get back on track, full compliance with procedures was essential. Everyone had to pull themselves together and be present in all operations. By doing this while also demanding that the eight life-saving rules were observed, the company would get back on track towards zero undesirable incidents.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Våge, S, “Effektivitet og konkurransekraft”, Pioner, no 1, 2014.

That called in addition for utilising risk analyses and exerting control of other organisational and technical barriers, along with PSI conversations. Together with the life-saving rules, these would set the standard for work in ConocoPhillips. Efforts to make safety improvements were to be resumed through good communication and a working culture where it was permissible to stop and ask questions.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Skjeggestad, K R, HSE manager, ConocoPhillips, “Beredskap er å være forberedt”. Pioner, no 4, 2017.

ConocoPhillips was named best operator on the NCS in the 2018 Gullkronen (Gold Crown) awards for its work with the Ekofisk field. Presented annually by consultancy Rystad Energy, these distinctions are presented to companies, teams or individuals who have shown an outstanding commitment on the NCS.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Rystad Energy is an independent analysis and consultancy company established in Oslo during 2004. The Gold Crown awards were first made in 2009. The jury citation stated: “The winner has displayed a high level of production efficiency over a long period, with an excellent HSE standard.”[REMOVE]Fotnote: “Vant pris som beste feltoperatør på norsk sokkel”, Pioner, no 1, 2018. This award must be viewed as confirmation that ConocoPhillips and the workforce on the Ekofisk field had succeeded in bringing the safety trend back on track.

Conclusion

Safety work is not about eliminating risk, but involves having good barriers – to protect against errors, hazards and accidents – as well as redundancy. But it is also about good communication between work colleagues and managers. Much be learnt by listening to what others have experienced and by sharing one’s own experience.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Skjeggestad, K R, HSE manager, ConocoPhillips, “Beredskap er å være forberedt”, Pioner, no 4, 2017.

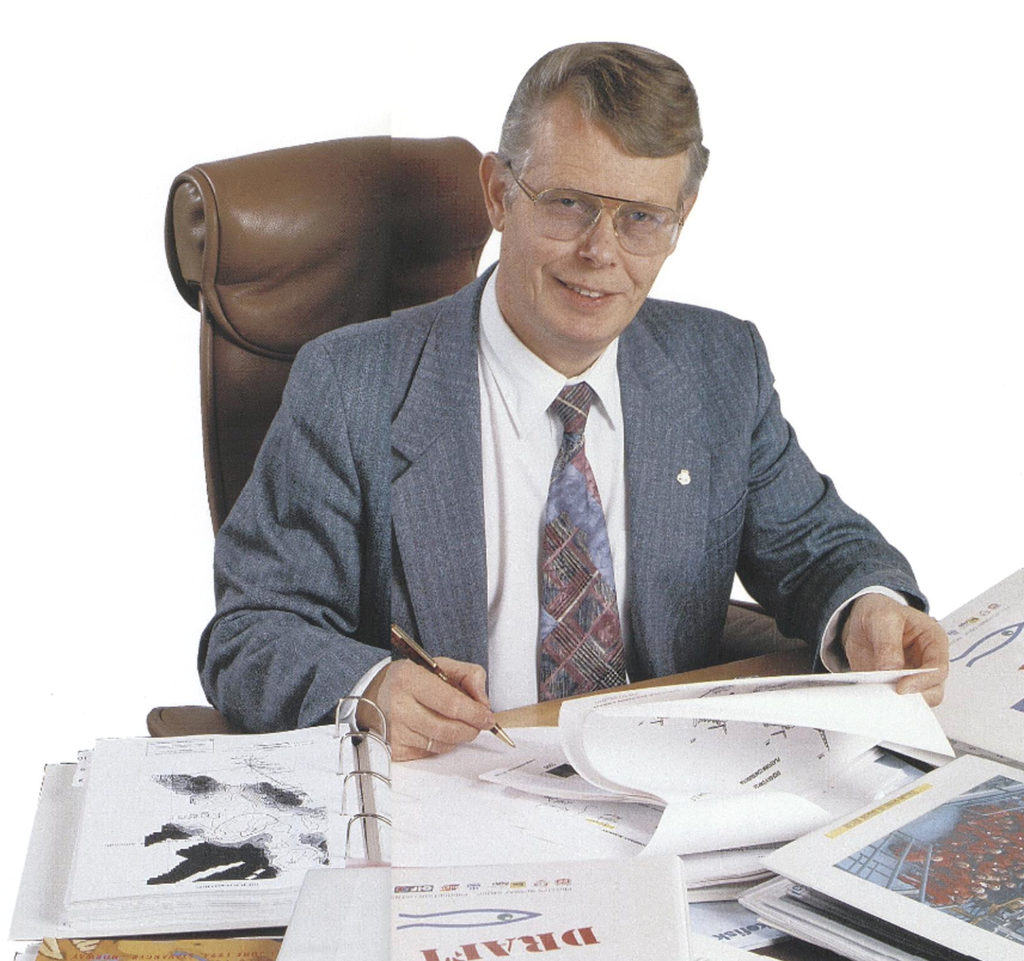

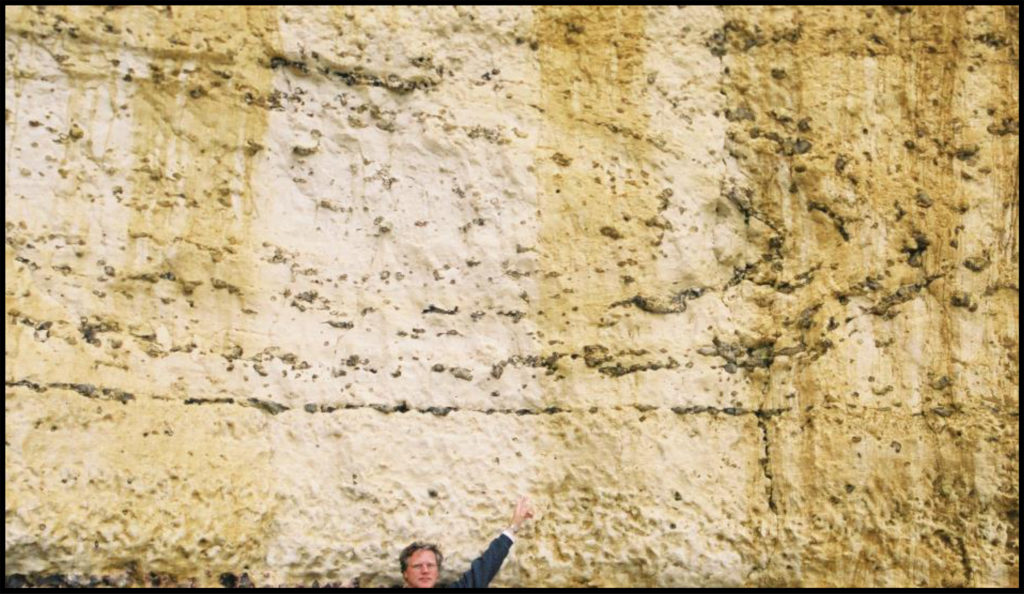

olje og gassveteran knut åm,

olje og gassveteran knut åm, Knut åm,

Knut åm,

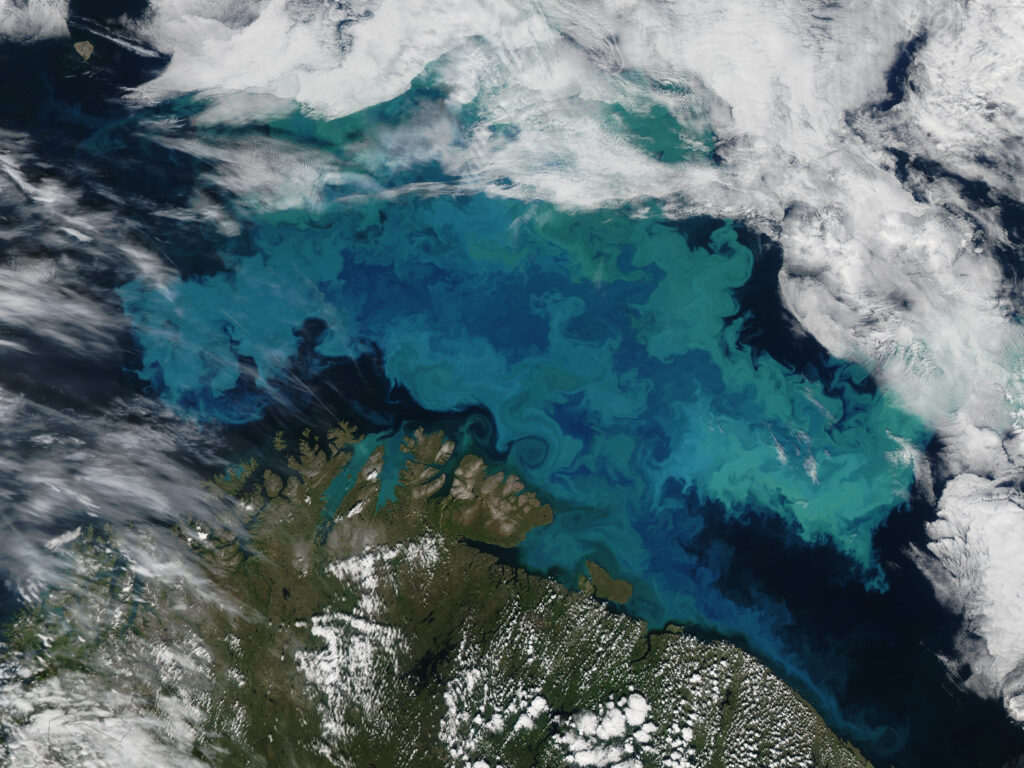

havets flass

havets flass havets flass,

havets flass, havets flass

havets flass havets flass,

havets flass, havets flass,

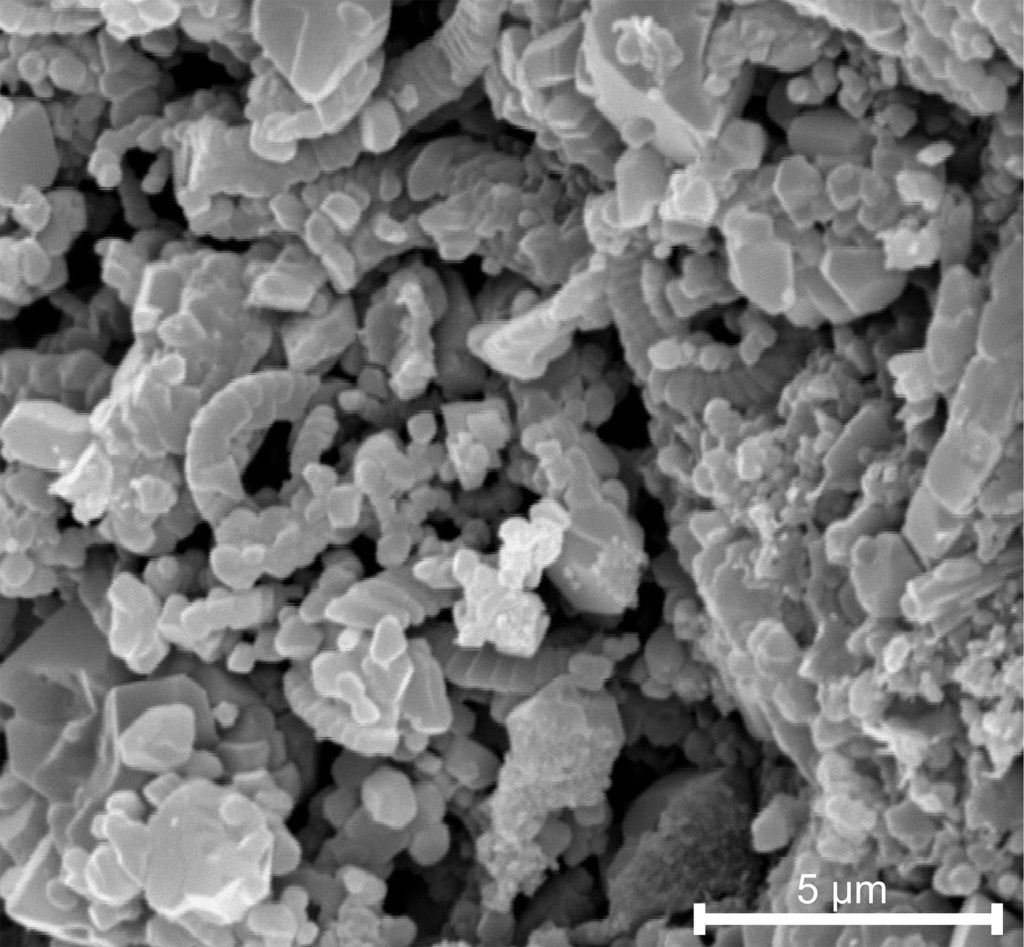

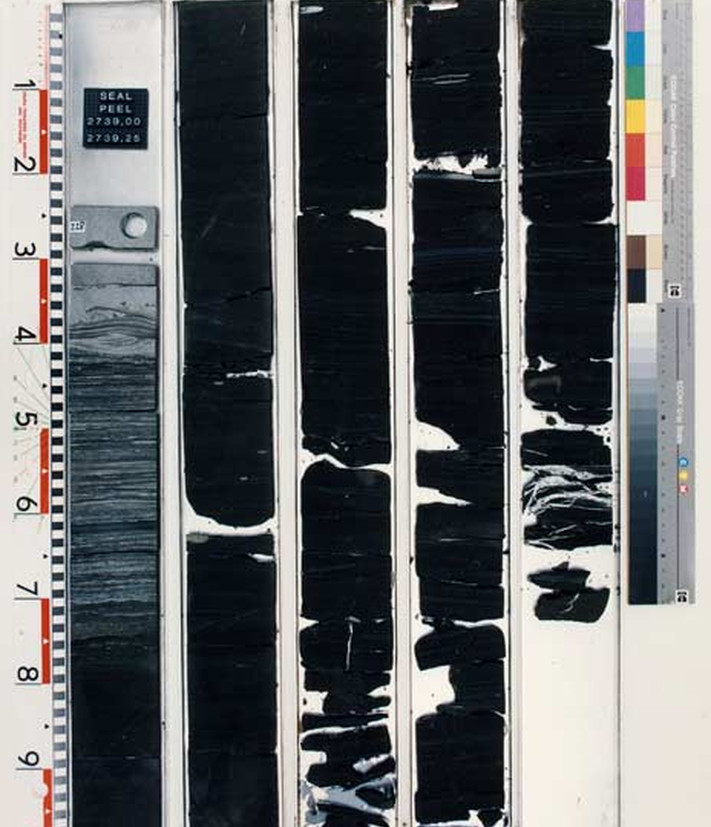

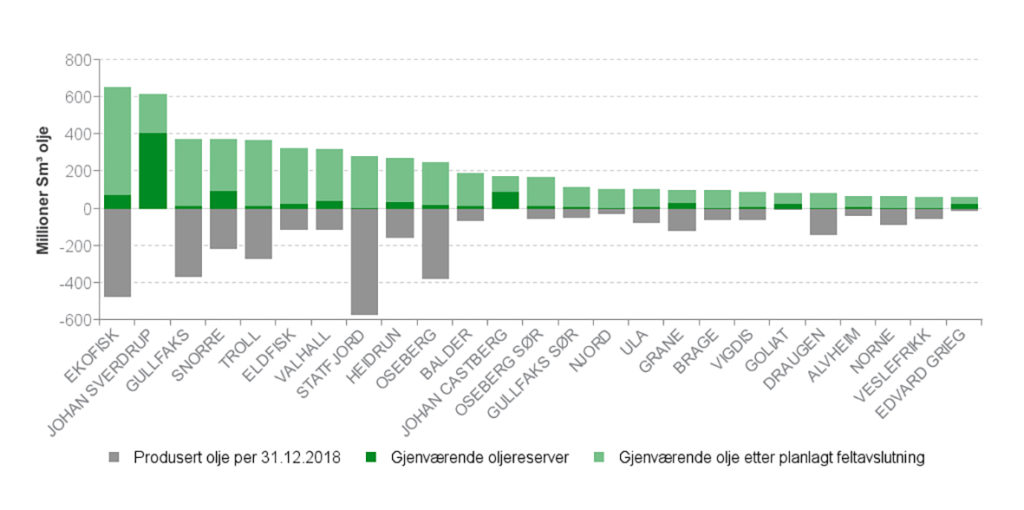

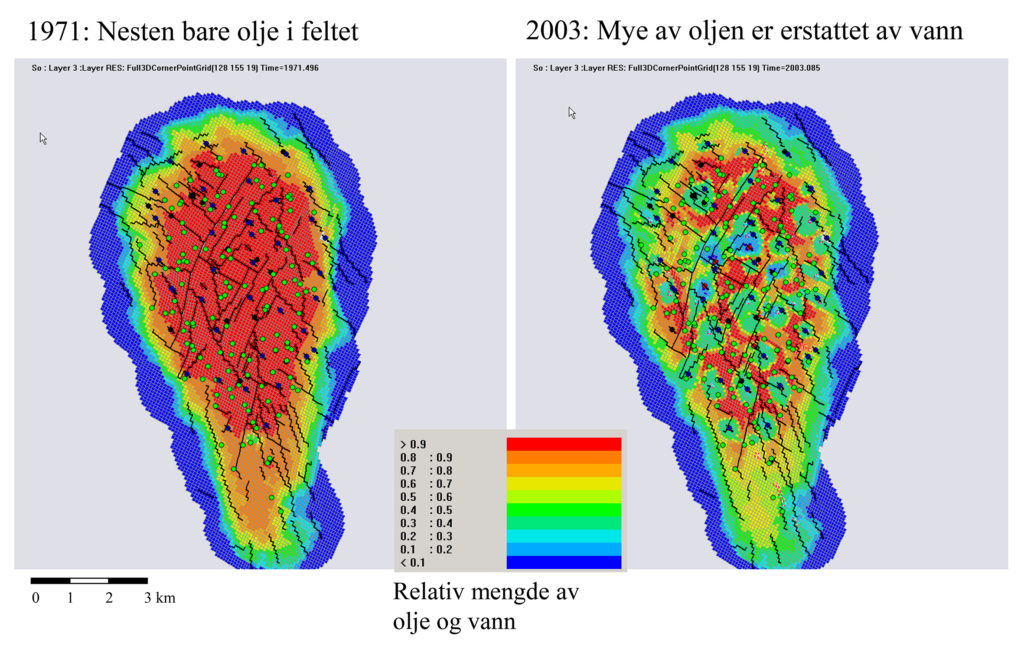

havets flass, Havets flass – geologien i Ekofisk, Vanninnsprøyting for økt utvinning, graf

Havets flass – geologien i Ekofisk, Vanninnsprøyting for økt utvinning, graf Havets flass,

Havets flass,