“Southern fields” collaboration

The aim was to get costs down and keep Norway’s oil industry competitive, prompting the three operator companies at the southern end of Norway’s North Sea sector to join forces in the autumn of 1996.

Phillips Petroleum, BP and Amoco wanted to improve production and costs as well as health, safety and environmental (HSE) results in the Greater Ekofisk Area and on Valhall, Hod, Gyda and Ula.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Amoco, BP og Phillips foreslår modell for framtidig samarbeid i Norge. Memorandum from Amoco, BP and Phillips.

Co-op project

A dedicated team comprising two full-time personnel from each company was established for this Co-op project covering the “southern fields”. Employee representatives were also involved.

More than 60 specific areas where improved cooperation could be possible were identified by this group. One principle was to use the same suppliers where this would be beneficial.

Others included standardising systems, tendering processes and procedures wherever practical, and the possible sharing of facilities. Greater experience transfer was also planned.

Union concerns

A positive view of the initiative was taken by the Ekofisk Committee and the two other “house unions” involved – the BP Offshore Committee (BPOK) and the Amoco Company Union (ABC).

These organisations felt that a collaboration would strengthen the position of their companies on the NCS and increase the utilisation of existing fields.

But they also made clear their opposition to any move towards joint operating companies. All three feared that this could create uncertain employment conditions for personnel and reduce operator responsibility for work on the NCS.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Letter to Amoco, BP and Phillips from the BPOK, the ABC and the Ekofisk Committee, dated 25 September 1996. ABC archive.

ekofisk-komiteen, historie, samarbeid i sør, 1996

ekofisk-komiteen, historie, samarbeid i sør, 1996“This could mean a disaster for employment,” Harald Sjonfjell, chair of the Ekofisk Committee, told local daily Stavanger Aftenblad. “Taken to its extreme, this collaboration could lead to a completely new operating company and I can then envisage big reductions in the workforce.”[REMOVE]Fotnote: Stavanger Aftenblad, 19. september 1996. –Katastrofe for sysselsettingen.

The companies could reassure the unions through the media that that there was no question of a new operations organisation or any workforce cuts. Savings would be achieved through closer cooperation over supplier contracts for goods and services. Only a small part related to manning. “We want to increase the value of the fields and extend their producing lives through this collaboration,” responded Amoco public affairs manager Sveinung Sletten.

But another version emerged in a letter from Amoco CEO Anders Mørland to the three unions, which said that the companies were considering all collaboration opportunities. These ranged from the “extremes” of stand-along joint projects to the formation of a jointly owned operating company.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Letter to the ABC, the BPOK and the Ekofisk Committee, represented by Amoco’s Ingard Haugeberg, from Anders Mørland, 28 October 1996.

Other unions expressed concern over these developments, with the Norwegian Organisation of Managers and Executives maintaining that extensive organisational changes like the Co-op project played down aspects of HSE work on the NCS. Unions were pushed to one side and presented with complete solutions which they had little time to comment on – and thereby played little part in the processes. The argument was that they were often presented with a fait accompli. If implemented, the Co-op plans would have major consequences for hundreds of employees.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Letter to industry and energy minister Grete Faremo from the Norwegian Organisation of Managers and Executives, dated 19 November 1996.

In the late autumn of 1996, the companies presented three different collaboration models – including a joint venture where the parent companies remained the employers. A jointly owned company which employees were transferred to was another option, along with single/multiple alliances where the companies remained but collaborated on hiring external resources.

The respective unions had prepared, and merged temporarily into a single body in order to be able to speak with one voice and avoid the employers playing them off against each other.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Info, interview with Ingard Haugeberg and the Ekofisk Committee, week 38,1996

After being initially positive to the idea of a collaboration, the three offshore unions were now willing to fight the creation of a common operations organisation. They interpreted signals from the companies to show that this was the way the wind blew, and the framework for the process indicated an intention to transfer activities to a joint body. In the event, such a company would rank in legal terms as a contractor and have to compete with similar players in the EU’s single market.

The unions made it clear that they would not accept a dedicated operating company, and the operators promised to take note. But their final plans showed that this was nevertheless their aim. That prompted the unions to put their collective foot down, and emphasised that they would shut down the whole southern end of the Norwegian North Sea unless the companies changed tack. Although this would have been illegal under Norwegian labour law, all three of the organisations were unanimous in threatening such action.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Interview with Ingard Haugeberg.

The companies accepted that the project could not continue against union opposition, and abandoned the idea of a merged company. Some of the plans were admittedly implemented, but not the ones which had much impact on the workforce.

Operating alliance

A form of collaboration between Amoco, BP and Phillips continued in 1997, with a three-year agreement on a “southern fields operating alliance” to cut costs.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Amoco Info nr. 14, uke 41 1998. Kjent under litt ulike navn, men offisielt og opprinnelig: Southern Fields Operating Alliance / Sørfeltenes driftsallianse (Ekofisknytt nr 13/1997) This involved a secretariat with one member from each company to coordinate and provide overall management of the project and to do preparatory work. Practical activities would be pursued by project groups and supported by area contacts at the partners.

Fibreoptic network and IT

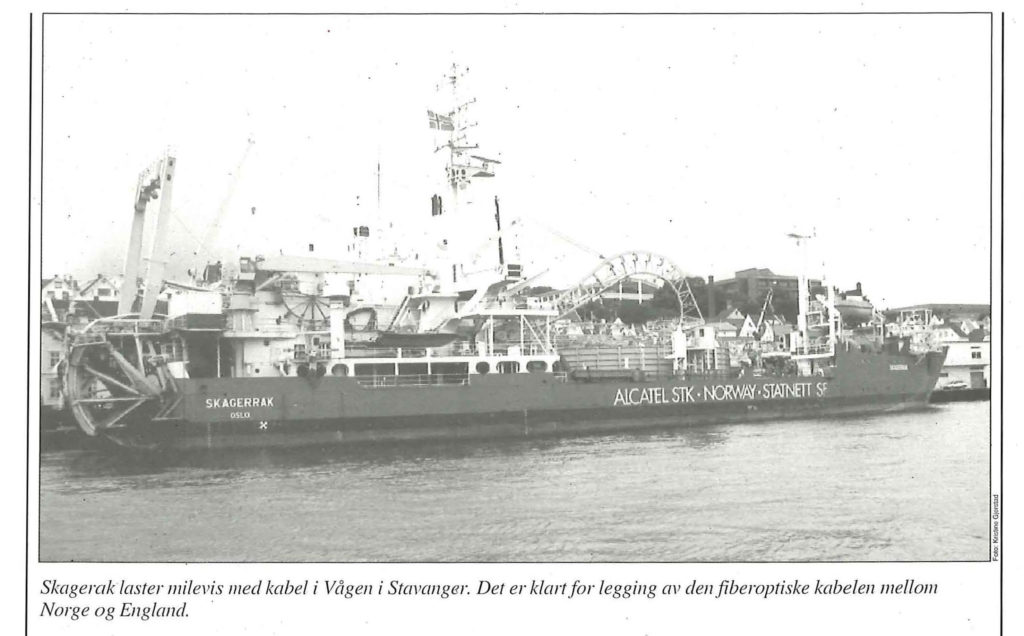

1999, hisorie, fiberoptisk kabel til ekofisk, forsidebilde, engelsk,

1999, hisorie, fiberoptisk kabel til ekofisk, forsidebilde, engelsk,One of the joint projects which came to fruition was the creation of a fibreoptic cable network between the southern fields and the Stavanger area.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Amoco Norway Oil Company, Annual report 1997. A letter of intent for this was signed in November 1997, and the cable was laid in 1999. It runs from Kårstø north of Stavanger to Valhall, via Draupner, Ula and Ekofisk. The network was extended on to the UK, but plans for a future links running from Valhall directly to Denmark, the Netherlands and Germany did not materialise.

A IT collaboration project was also implemented. The operating alliance and a number of other oil companies developed a sectoral network operated by an external supplier. This simplified the flow of information between the operator companies, the service and supplier industry, and others involved in joint projects.[REMOVE]Fotnote: Meland, Trude, “Search for collaboration and union opposition”, Valhall industrial heritage, 2015,

Collaboration on emergency preparedness

Perhaps the most important result of the collaboration process was the introduction of joint emergency preparedness arrangements. This involved Phillips and BP joining forces in 2001 to improve their use of response resources at the southern end of Norway’s North Sea sector.

Their agreement covered joint preparedness analyses and requirements as well as documentation and collaboration over response drills. An improved overview of emergency response resources in the area and agreement on the division of costs also formed part of the collaboration.

Emergency preparedness for this part of the North Sea covered cooperation over critical incidents, such as a person falling overboard when working above the open sea. Other examples included people in the sea after a helicopter crash or emergency evacuation, a collision threat, acute oil spills, and fires and personal injuries requiring external aid.

This collaboration made it possible to reduce the number of standby vessels on Ekofisk from three to two.[REMOVE]Fotnote: EkofiskNytt, no 4, “Beredskapssamarbeid på sørfeltet”, week 17, 2001.

Storting approves Ekofisk IIChemical spill to the sea