The discovery which changed Norway

The company wanted to terminate its exploration programme, and several geologists at the Oslo office were asked to pack up and return home. But one well remained to be drilled under the terms of the licence. Although the mood in Bartlesville was to drop this commitment, the Phillips group still had Ocean Viking on charter from Odeco and the day rate had to be paid whether or not it drilled. No other oil companies were interested in taking on the rig, and Phillips decided to drill the first well in block 2/4 at the centre of the North Sea – close to Norway’s boundaries with the Danish and British sectors. The seismic data showed a big structure pushed up by an underlying salt dome.

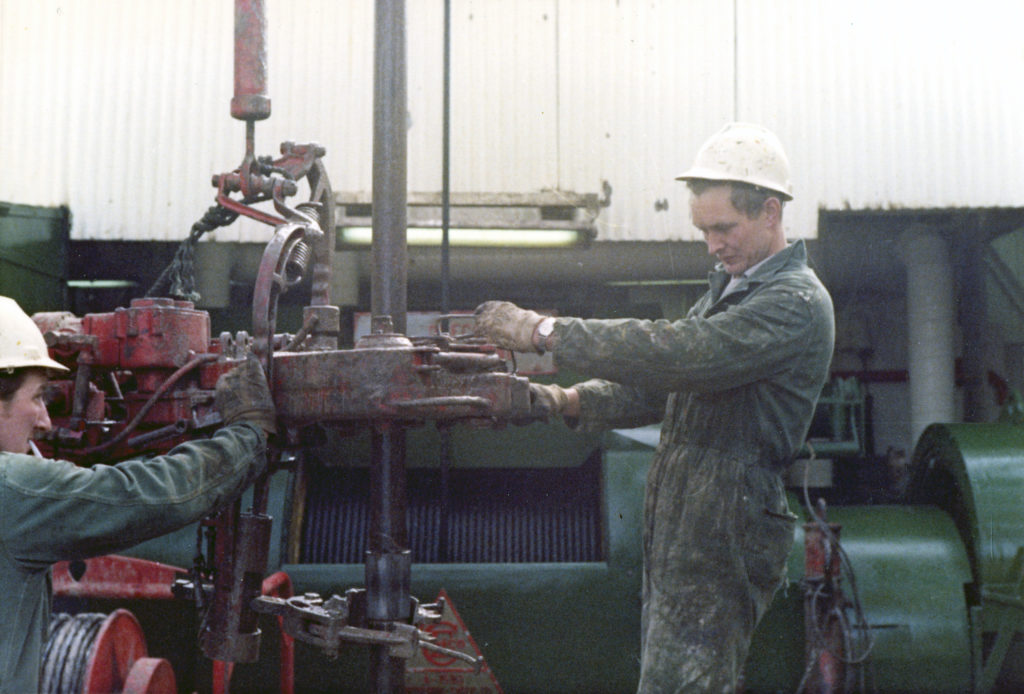

Tidsvitne til funnet i 1969,

Tidsvitne til funnet i 1969,After 10 days, the drill bit had reached a depth of 1 662 metres and encountered two formations under different pressures. The fluid column intended to balance pressure in the well was not heavy enough, and leached into the formation. A kick occurred when the bit encountered the highest pressure. The drillers sought to stabilise the well by throwing in plastic, horse manure, nutshells and more, but to no avail. Their only option was to plug the well, move 1 000 metres and start again. That happened two days later, on 18 September, when the big discovery well was spudded. On 25 October, at a depth of 3 081 metres, the downhole gas volume suddenly increased sharply.

Gisle Gislason, Anders Sebø og Ståle Salvesen på boredekket på Ocean Viking, 1969

Gisle Gislason, Anders Sebø og Ståle Salvesen på boredekket på Ocean Viking, 1969Roustabout Ståle “Salvi” Salvesen was enjoying a night-time cigarette by the drill floor when brown strips suddenly began to emerge from the sand shaker he sat next to. Salvesen did not pay much attention, everything seemed to be in order. The viscosity and weight of the drilling mud was stable. But the volume increased, and he noticed a distinctive smell. He phoned driller Einar Grønlie Olsen, who also thought this was nothing important.

Then Dick Berg, a Canadian with Norwegian roots, passed by carrying a smoke and a coffee cup as usual. He said: “Salvi, something smells here.” It was 02.30. They agreed that drilling superintendent Ed Seabourn had to be roused from his bed on the floor below.

Seabourn was not best pleased: “Salvi, you’d better have a damn good reason to wake me up in the middle of the night.” But he came up in pyjamas, slippers and dressing gown, and climbed onto the shaker to get a better look.

He slipped on the greasy footing and fell over, coating gown and pyjamas with mud. But that was unimportant. When the shift changed at 06.00, he gave a speech to tell the crew that a historic oil discovery had been made. The gas pressure was huge. When Salvi ignited the flare boom to burn it off, the whole structure jumped up and down and the entire rig shook.

Oslo daily Aftenposten wrote on 28 October that an oil and gas discovery had been reported, but Phillips would confirm nothing because two-three weeks of drilling remained to be done.

Bad weather now created problems for the rig. A winter storm in early December, with waves 15 metres high, put a stop to logging and meant the equipment had to be pulled from the well. Anchors came loose and Ocean Viking began drifting. The position was dramatic. With some of the anchors dragging, the derrick was fully loaded with stands of drill pipe and in danger of overturning. Part of the crew was therefore evacuated by helicopter.

After about a day, the weather calmed down and the rig could be towed back into position without too much damage. Logging resumed on 16 December and the necessary tests were performed.

The well was abandoned on 23 December. On the same day, Olav K Kristiansen in the Ministry of Industry’s oil office had the pleasure of taking the phone call which reported the find.

Nevertheless, the event which was to transform Norway and make it an oil nation only became publicly known on 2 June 1970 with a press release from Phillips.

The discovery well was the 38th to be drilled in the Norwegian North Sea – and 25 October 1969 is considered to be the date when the Ekofisk discovery was made.

Gas and condensate discovered in CodEyewitness to the 1969 discovery