The Ekofisk Committee – an unusual union

The Norwegian Confederation of Trade Unions (LO), which was the key player on the mainland, found the oil industry challenging and failed to establish its position in the initial phase. While it vacillated over which of its affiliated unions should organise the offshore workforce, the Ekofisk Committee emerged as a substantial external competitor. This body covered most of the operator personnel and other employees on the field.While it vacillated over which of its affiliated unions should organise the offshore workforce, the Ekofisk Committee emerged as a substantial external competitor. This body covered most of the operator personnel and other employees on the field.

Øyvind Krovik, known as the “father” of the Ekofisk Committee, has given his version of its formation. He chaired the committee and its successor, the Collaboration Committee for Operator Unions (OFS), from 1974 to 1990.

Conservative who became a union leader

The unusual aspect of Krovik’s story, in a country where unionism was closely associated with social democracy, is that he was a Conservative Party supporter who created a new union.

Coming from a home where politics was much discussed, he was already politically active when, newly qualified, he secured his first job as an electrician/roustabout on Ekofisk in 1974.

The Vietnam War was a hot topic, and Krovik had helped to form the Committee for South-East Asia, a right-wing organisation. He became chair of the Young Conservatives in Haugesund north of Stavanger, and then in the wider Rogaland county.

lasting, lossing, supplybåt, ekofiskkomiteen,

lasting, lossing, supplybåt, ekofiskkomiteen,After his initial training with Phillips Petroleum Company Norway (PPCN) on land, he was sent offshore as assistant to an electrician on Ekofisk 2/4 C. His experience of working conditions on ”Ekofisk Charlie” made an impression on him. He found that people were treated very differently, depending on which company they worked for and their contract of employment. This seemed inequitable.

The platform was organised with Phillips, as operator, having a drilling supervisor in charge. He supervised drilling contractor Morco, which was responsible for everything done on the drill floor and also employed the crane operators. Meals were prepared, cabins cleaned and the laundry operated by the catering contractor. In addition came a number of construction companies, with Spain’s Umech as the biggest.

The employees were a mix of Spaniards and Britons, who worked completely different tour patterns to the Norwegians. Some were three months on, one off. With new contracts for each tour, it was not certain they would return if they misbehaved.

Krovik regard this as unjust compared with his own pattern of eight days on and eight off. It had earlier been seven on and seven off. Contractual and working conditions were entirely different – the Spaniards, for instance, came out by supply ship, while the Norwegians took a helicopter flight out.

Accommodation was a story in itself. Krovik lived in the ”temporary quarters”, a two-storey structure accommodating 50 people with four WCs and four showers between them. When people got up at the same time, accessing these facilities was not easy. The permanent accommodation had four-bed cabins, with shared showers and WCs in the corridors. By contemporary standards, that was not good either. Senior personnel had a double cabin with a shared WC. Incredibly enough, the drilling supervisor opted to live on the drill floor, in a small hut with a bed, so that he could keep a constant eye on the work.

Background for the Ekofisk Committee

In 1973, the year before Krovik joined Phillips, employee representatives had been elected on Ekofisk – roughly in the way classroom representatives are elected at school, Krovik says. This was not an independent union branch with membership, but an association subject to Phillips – the type of organisation known as a “company union” in the USA. After the elections, a kind of collective bargaining system was introduced which made provision for the formal relationship between the Phillips management and the workforce. The company called this in-house association the Phillips Petroleum Norway Offshore Employee Committee (PPOEC). It was ready to discuss such issues as pay and to help with tax matters. At the same time, unionisation was discussed in the summer of 1973 among the Norwegian drilling personnel on Ekofisk under the leadership of Tom Nordahl.

The result, known as the Oil Workers’ Union, got going in reality during 1975 and was initially a branch affiliated with the LO and reluctantly lumped with the Norwegian Seamen’s Union. Since personnel on the fixed Ekofisk installations did not regard themselves as seafarers, this union never succeeded in playing an active role on the field. Employees on the mobile rigs, which were defined as vessels, paid the lower Norwegian tax rates applicable to seamen. These did not apply to Ekofisk workers, but they received a kind of compensation for that. Their contracts of employment stated that, if seamen’s tax were extended to the platforms, their pay would be reduced accordingly – an argument for joining the Seamen’s Union. The time was thereby ripe for a new option. One of the most important reasons for establishing a proper union, in Krovik’s view, was to get Norway’s Worker Protection Act extended to the fixed installations.

Phillips’ refusal to discuss the working environment, working time or worker protection with its employees was a problem. With backing from the Act, the workforce could demand the right to discuss such issues.

One employee, for example, had worked almost 50 per cent overtime. What would happen if personnel refused to do that many extra hours? The PPOEC had little power to make its demands felt with Phillips. It had neither a strike fund nor access to legal help. This got him going, Krovik recalls. He was discussing these questions with one of the operators, a former ship’s officer, when the latter gave him a piece of his mind: ”Yes, you’re just like the others. You talk big, but do nothing”.

Krovik then decided to try to persuade the others to join him in a new union. ”If you get things going, I’ll join you,” his colleague told him. A discussion followed with PPOEC officials on Ekofisk 2/4 B and D and at the Ekofisk Complex. Most agreed that they were not seafarers and that the Seamen’s Union was not appropriate.

Working time provisions and protection from dismissal for seafarers were not felt to be appropriate for a production platform by the oil workers. Nor was LO affiliation necessary. The PPOEC representatives gave Krovik the green light to try establishing a new union. But the person with the list of people prepared to join the Seamen’s Union refused to pass it over – so full agreement was not established.

Bakgrunn for første husforening på Ekofisk, logo,

Bakgrunn for første husforening på Ekofisk, logo,An election was held shortly afterwards, when Krovik became chair of the executive committee. Virtually everybody joined and paid their dues. The PPOEC name was taken over and quickly simplified to the Ekofisk Committee. From 1976, it adopted the Norwegian version – ”Ekofisk-komiteen” – as its official designation.

The Ekofisk Committee was ready to ask for negotiations with Phillips, but lacked the necessary experience. Krovik had not received any schooling in the Worker Protection Act in the Conservative Party. The party’s local office in Stavanger recommended that he contact lawyer Tormod Våland.

The latter was willing to help. He found the combination of the oil industry and the Worker Protection Act highly interesting, and made himself available – while also demanding a commitment in return.

Cooperation with the NPD

When the first fixed platforms became operational, responsibility for the safety of the living accommodation, rescue equipment and so forth rested with the Norwegian Maritime Directorate (NMD). The Norwegian Petroleum Directorate (NPD) was created in 1972 and, as it began to become properly operational, started to engage with working conditions on the offshore facilities.

ekofiskkomiteen, logo,

ekofiskkomiteen, logo,Krovik quickly established a good dialogue with this agency. In his view, Phillips was not particularly happy about the NPD poking its nose into what went on in the company’s workplace. But the employees saw the possibility that the directorate could serve their cause. One aim was to get it established that they were industrial workers, not seafarers. A benefit such as the lower seafarer’s income tax was of secondary importance compared with seeking to raise pay for oil workers.

Another goal involved getting the Worker Protection Act, with its working time provisions and safeguards against dismissal, extended offshore – something the NPD was also interested in. According to Krovik, the NPD appeared to be competing with the NMD on who had authority over the fixed installations. It had the Ekofisk Committee’s full support in this struggle.

With legal advice from Tormod Våland, the Ekofisk Committee went through the Worker Protection Act chapter by chapter in order to adapt it for the fixed North Sea facilities. The NPD then weighed in and extended the Act to these installations. In that way, the Ekofisk Committee helped to clear the way for applying this legislation offshore. The chapter on safety delegates was introduced in 1975.

Being an elected shop steward for the Ekofisk Committee was no bed of roses, and Krovik was virtually persecuted by certain supervisors on the field. As an electrician, his shift ran from 06.00 to 18.00. During that time, all union work was forbidden. It had to be done in the evenings. The shop-steward job required him to visit neighbouring platforms, but he was not allowed to take a helicopter. Instead, Krovik had to be lowered by basket to a supply ship. He would then return the same way, tailored to the routes taken by these vessels. This often meant carrying on into the late evenings and at night. So it was a victory when he managed to get permission to travel back to his own platform after 06.00, because a lot of people were shuttled around at that time.

Some of the supervisors alleged that Krovik was pursuing union activities during working hours, and he was carpeted for that several times and criticised for it.

A newly appointed American supervisor gave him a very poor personal assessment – even for first aid, where he was well trained. Krovik refused to sign the form. Finally, he went to the superintendent and requested a copy of the assessment so that he could take the matter up with the union and possibly go to court. He heard no more, but the next superintendent to come offshore said to him: “We’ll fix this while that other guy’s not here, because this is completely out of order.” A new form was completed with an acceptable assessment – sufficient to earn a pay rise, which was not particularly popular when the other superintendent turned up again.

Union office on land

Krovik felt that he lived on a knife edge many times. Conditions improved in late 1976 when the personnel manager offered him the full-time job of chief safety delegate with an office on land.

By that time, the Worker Protection Act had been extended to the oil industry, and it was important that the elected safety delegates and union officers offshore could ensure that legal and regulatory provisions were being observed. The NPD used the shop stewards as a party in consultations.

The office at the Tananger base was also utilised for overnight accommodation. Krovik lived on Karmøy, on the other side of the wide Bokn Fjord from Stavanger, but felt he could not use union dues to pay for a flat near the base.

Dues were low, and the money which came in had to be spent on legal assistance. Staying overnight in a hotel was only acceptable when formal negotiations were being pursued with Phillips and the latter footed the bill.

As the union’s finances improved, Krovik was able to utilise a flat in the Stavanger area. He could then invite NPD staff to discuss a number of issues, and a very sociable time was had.

Personnel at the regulator were new to the job, and welcomed the opportunity to learn more about what happened out on the platforms.

From worker protection to working environment

Norway’s Working Environment Act was extended offshore in 1977, but Krovik did not feel this meant much for the Ekofisk workforce because they were already covered by the Worker Protection Act.

But a review of the way the two statutes were to be applied was required, and a commission chaired by civil servant Kåre Halden was appointed to carry out this comparison.

Its members included Odd Friberg, known as the “father” of the Worker Protection and Working Environment Acts, who had written all the interpretations and who was an appeal court judge as well as head of legal affairs at the Norwegian Labour Inspection Authority.

Krovik was also on the commission, but Phillips had no representation – which its management was not happy about. Key LO personnel took part, as did the Norwegian Employers Confederation and specialists from the local government ministry.

This proved an instructive process, in Krovik’s view. Two official reports were published, and a number of exceptions were created for the oil industry. Although most of the requirements of the Working Environment Act had already been introduced, Krovik felt that its introduction raised standards. Nevertheless, the effects were perhaps greater for personnel in the other oil companies and contractors than for employees in Phillips.

In Krovik’s view, it was “fortunate” for the establishment of the Ekofisk Committee that the union was dealing with an American company which wanted nothing to do with press or government. That gave the union scope to get established. It would have met harder opposition in Norwegian companies such as Statoil or Norsk Hydro, which were already in national employer associations. Forging an informal alliance with the NPD at an early stage was also advantageous. This benefited not only the committee but also the directorate in its rivalry with the NMD.

OFS established

Personnel on Statfjord also began to organise while the A platform for this field was under construction at Stord south of Bergen in 1976. Mobil was operator there during the early decades.

Krovik visited Stord and the Mobil employees, who had offices on a passenger ship, in order to talk about unionisation and whether they wanted to cooperate with the Ekofisk Committee.

Even before that, unionised personnel at the Shell refinery in Risavika near Stavanger had contacted Krovik and established a collaboration. They in turn had contacted the Mongstad and Slagentangen refineries, resulting in the emergence of a small oil group. However, the refinery personnel eventually withdrew after the Statfjord employees became involved, because the collaboration then became too oil-related. Some wanted to join the Norwegian Oil and Gas Employees Association (NOGMF), an LO offshoot. This incidentally changed its name in 1977 to the Norwegian Oil and Energy Employees Association (Noemfo) and became the first Norwegian union to go bankrupt.

The Statfjord Committee was established in 1976 and quickly renamed the Statfjord Workers Union (SAF) – a more conventional title for such a group. While the SAF ranked as an independent body, the Ekofisk Committee was a big brother by comparison. After Elf employees on Frigg also formed the Elf Aquitaine Norway Offshore Union (Eanof) in 1977, these three established a cooperation committee. This provided a forum where shop stewards could meet and discuss issues. Towards the end of the year, more formal, binding rules were adopted and it was named the Collaboration Committee for Operator Unions (OFS).

As an independent umbrella organisation, the OFS had no affiliation with the LO or other Norwegian union confederations. Nor were its member unions on the various fields merged.

They negotiated at local level with their respective operator companies on pay and working conditions, which varied from company to company.

In 1979, rules were adopted for the OFS with a view to strengthening collaboration and helping to coordinate matters of common interest. The decision was taken to establish a single collective pay agreement for all operator employees.

Relations with the Spaniards who were employed on developing Ekofisk were less harmonious. These foreign workers were not happy with the Working Environment Act. This legislation was, of course, supposed to protect all employees from exploitation. But the Spaniards had no desire to change the tour pattern of three months offshore and one at home. They regarded their offshore assignments as construction work lasting two-three years, by which time they would have saved enough money to open a shop at home.

In reality, implementing the Working Environment Act and reducing working hours meant a pay cut for them. The unions thereby found themselves in opposition to the Spanish workers.

The Ekofisk Committee took the view that a standard had to be set for working time arrangements offshore. Norwegian industrial companies engaged as offshore contractors were interested in ensuring that their employees had orderly conditions along the same lines as for operator personnel. Companies in Norway could not compete with the terms governing the Spanish workers. Many discussions have since taken place over who falls within the Working Environment Act and who does not.

The first industrial disputes

Krovik experienced the first threats of conflict when the Ekofisk Committee was to negotiate a collective pay deal. The talks were conducted in English, but this gave rise to a number of misunderstandings, and Krovik therefore proposed that they should switch to Norwegian. Phillips said no.

According to the Working Environment Act, the employer representative must be a person with authority who can agree or reject matters and who has financial authorisations. If it was to negotiate in Norwegian, Phillips would have to go a long way down the ranks before finding the first native speaker in its hierarchy.

Krovik wanted the union to negotiate with the chief executive or, failing that, the person in charge of the Greater Ekofisk Area. But how could that be done in Norwegian? His decision was straightforward: “OK, we’ll negotiate and go straight to a warning of strike action. We’ll down tools over the language.” He had already checked with Reidar Webster, the deputy national mediator, and asked: “If we end up with you, do we only talk Norwegian there?” And the answer was equally direct: “Yes, we speak only Norwegian here and nothing else. If anybody talks a different language, it has to be translated for me.” “Great,” said Krovik. “We’ll be there.”

The Ekofisk Committee notified a strike and, in line with Norwegian labour law, the two sides were called in to Webster for mediation. These talks were conducted in Norwegian, with interpreters for the Americans. The upshot was that collective pay bargaining was henceforth conducted in Norwegian – which made it easier for locals to make headway.

Nopef enters the arena

Nor did the LO sit idly by, either. The seamen’s union alleged that the Ekofisk Committee obstructed its efforts to organise people on the field and threatened a boycott.

In these circumstances, the confederation was not convinced that the seamen were the right horse to back. Senior official Tor Halvorsen announced in December 1976 that the LO would propose the creation of a separate oil and petrochemical union.

arbeidsliv, fagforeninger, logo, Første fagforeninger i oljeindustrien,

arbeidsliv, fagforeninger, logo, Første fagforeninger i oljeindustrien,This was approved a fortnight later, with geologist Lars Anders Myhre at the NPD following up the plan. A number of LO unions were asked to assess establishing a new organisation.

Several people from the confederation also tried to persuade Krovik that joining the LO was the only right way to go. He was offered the post of chair in an interim executive committee. This occurred before the Statfjord and Frigg personnel had organised.

During the process, Krovik travelled to Tønsberg near Oslo for a meeting. A story that the Ekofisk Committee was to join a new LO union was leaked to the press and created ructions.

Krovik had to call his members on the field to say the leadership had no intention of going over their heads in any area, and that this was just nonsense. He was not changing political affiliation to the Labour-supporting LO that easily.

A vertical organisation was chosen for the new LO union – in other words, all employees in the oil and petrochemical industry would be grouped together in a single organisation. The vision was to establish a labour union which could be a mirror image of the oil industry, from upstream exploration drilling and production to downstream operations such as refining and administration. An organisation like this would give the workers great negotiating strength with a very effective strike weapon, since all stages in the production process could be crippled. The plan was processed in record time, and the LO secretariat had approved the creation of the Norwegian Oil and Petrochemical Workers Union (Nopef) by 31 January. Myhre was elected president despite having no offshore experience. But he had the resources and background for building a union.

Krovik attended one of Nopef’s interim board meetings at Bryne near Stavanger where the first LO union for oil workers was established. Personnel in drilling contractor Morco joined fairly soon, and became a kind of backbone for Nopef. “I’d had a lot to do with Myhre,” recalls Krovik. “I think that, if you chatted calmly with him in private, he’d admit that we’d never have come so far, so fast without the Ekofisk Committee and the OFS. “But the Ekofisk Committee could never have joined the LO, as it did later, as long as I was there. We started it, and established the identity of what became the OFS.”

Extended to all jobs

The Norwegian government demanded in 1980 that an organisation had to have a national scope in order to pursue collective pay bargaining. Only then did the OFS became a proper union. In Krovik’s view, that took some of the edge off the LO’s approach. Nopef had expected to be alone with that role in the North Sea. His background in the Conservative Party proved beneficial in this context. He visited the Storting (parliament) twice a year to lobby in its corridors.

Industrial action was threatened by the OFS unless it was recognised as a national union. But the matter was resolved through a letter from the ministry. The OFS was certainly not afraid to threaten stoppages. Illegal action on Statfjord in 1981 marked the beginning of a long series of strikes. This willingness to down tools proved a success – wages rose 30-35 per cent in the 1981 settlement.

That victory was due not only to the OFS, but also to weak organisation among the employers. The foreign oil companies were used to doing as they pleased, and opposed government intervention and organisation. Surprisingly enough, this was sorted out by a Conservative government headed by prime minister Kaare Willoch. After the 1981 pay settlement, it insisted that the companies had to adapt to Norway’s labour market traditions.

Phillips and the others had no choice. They converted their existing organisation to the Norwegian Operator Companies Employers Association (Noaf), which joined the national employer confederation and became the forerunner of today’s Norwegian Oil and Gas Association.

Willoch threatened that oil companies who refused to join had no future on the Norwegian continental shelf and would face consequences in terms of future licence awards, tax rules and the Labour Disputes Act. This became known as the Willoch doctrine.

Given the good results achieved by the OFS in 1981 and the tighter rules introduced by the government, more associations and occupational groups found it interesting to sign up. The collective agreement on pay and conditions negotiated by the OFS was the magnet. A number of others wanted to achieve the same working conditions.

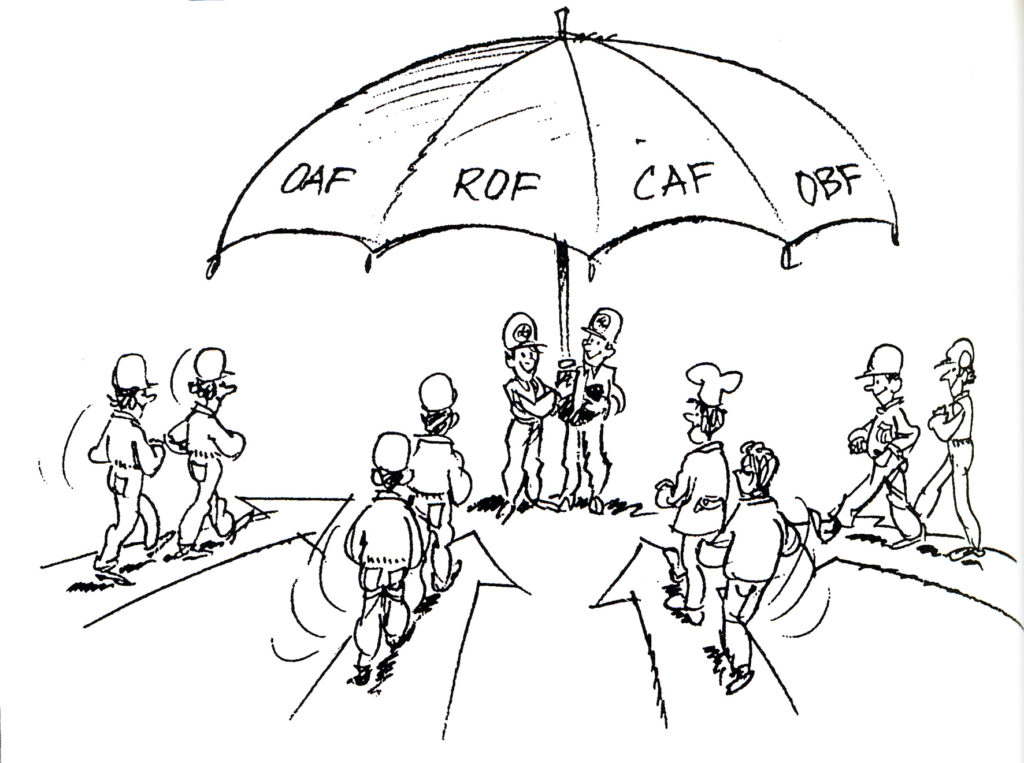

arbeidsliv, husforening, fagforening, ekofisk-aksjon, streik, paraply, ekofiskkomiteen,

arbeidsliv, husforening, fagforening, ekofisk-aksjon, streik, paraply, ekofiskkomiteen,First off the mark were the catering workers. The system they were organised in refused to take them seriously. Krovik travelled around the platforms and got them to join the Catering Workers Union (CAF).

An extraordinary national conference in 1982 resolved that the OFS would be a federation for all occupational groups in the North Sea, not just operator personnel.

The Union of Shipping Company Employees (ROF) and the Oil Drillers Union (OBF) were also incorporated, and the organisation changed its name to the Federation of Offshore Workers Trade Unions – retaining the OFS abbreviation.

No unions – half the pay and twice the working hours

“Many people say jokingly that: ‘if it hadn’t been for those of us who started this, we’d have had half the pay and twice the working hours’,” observes Krovik. “It wouldn’t have been quite that bad, but pay and conditions would not have been at today’s level.”

Pursuing union activities on Ekofisk eventually became easier. Krovik reports that drilling personnel originally provided the supervisors on the platform, and came straight from the jungle. “They had a language which was 50 per cent swearwords. When they abused you, you had to learn to respond in kind. You could do that as an operator employee, while contractor personnel simply had to take it. “When the process people took over, they brought a completely different culture with them. The supervisors who came over from the States, like Mike McConnel, were a different type, who carried weight. They saw that the unions existed and had legitimate demands.”

McConnel served as drilling and production manager on Ekofisk to gain experience before taking over as CEO in Norway, and Krovik reports that they had some conflicts.

“These resulted at least twice in mediation,” he says. “Those of us who spearheaded the dispute then took a trip with management to Flekkefjord [south of Stavanger] on a coach with a bar.

“Arriving at a hotel, we spent the evening discussing all aspects of the conflict. The atmosphere became convivial, and the following morning the message was: ‘Now we’ll put what’s past behind us, we’ll forget that. We’re standing here now and then we’ll move forward. What do we do now to sort these things out?’. [McConnel] had these win-win theories.”

Krovik himself thinks it was unusual to be a union leader with a background in the Conservative Party, and has reflected over this:

“People believe Conservatives are huge egoists, but I’ve demonstrated the opposite through my commitment. I’m more concerned that individuals have rights. I believe that, in the specific union in the particular system, opportunities must exist for individual tailoring. That was my driving force.

In my view, workers do better with that type of thinking than the LO mindset, where every collective pay agreement has to be cut from the same cloth. But the OFS itself has been run by Labour supporters, so the organisation hasn’t been characterised by any clear party policy.”

Sources

This article builds primarily on an interview with Øyvind Krovik by Kristin Øye Gjerde on 31 January 2002 in the Ekofisk Industrial Heritage project.

Myhre, Lars Anders, Svart gull og rød flamme, Nopef 25 år. 2002.

Ryggvik, Helge and Smith-Solbakken, Marie, Blod, svette og olje. Norsk Oljehistorie, volume 3, 1997.

Smith-Solbakken, Marie, Oljearbeiderkulturen. Historien om cowboyer og rebeller, 1997.

Interview with Egil Lima, 26 November 2001 – Ekofisk Cultural Heritage (extract).

Interview with Teddy Broadhurst, 2 December 2001 – Ekofisk Cultural Heritage (extract).

Interview with Egil Berle 20 June 2003 – Ekofisk Cultural Heritage (extract).