How oil changed the Stavanger region

New opportunity

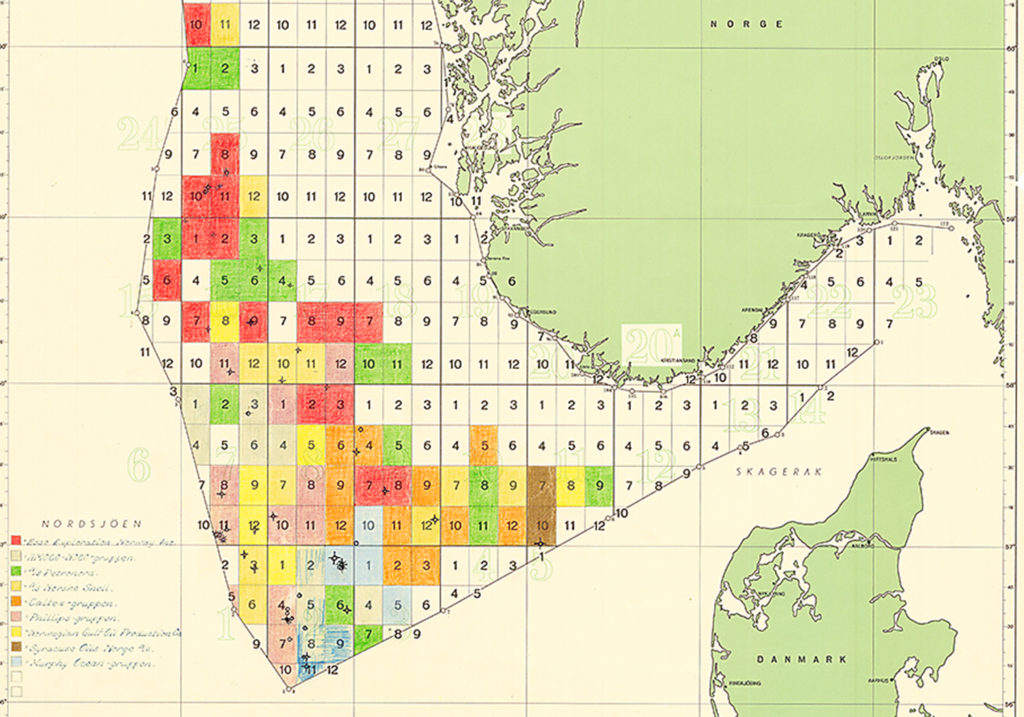

Norway’s first offshore licensing round was announced in 1965 and a new opportunity opened for the port city as the American oil explorers looked for good base areas to support their operations. At the same time, members of the local business community – such as shipowner Torolf Smedvig – were seeking new activities. So were politicians, particularly mayor Arne Rettedal.

They were very ready to make provision for the foreign oil prospectors with base sites, homes for their expatriate personnel, schools for their families and so forth.

sokkelkart, illustrasjon, blokker, lisens, forsidebilde, engelsk,

sokkelkart, illustrasjon, blokker, lisens, forsidebilde, engelsk,Stavanger thereby became established as a petroleum centre even before the first commercial discovery was made on Ekofisk in the late autumn of 1969. The city stood ready to take on the role of Norway’s “oil capital” when the first crude began to be produced in 1971. It has had the highest density of oil workers in Norway ever since.

Official recognition

Stavanger was officially recognised as an oil centre when the Storting (parliament) voted in 1972 to locate new state oil company Statoil and the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate (NPD) there.

Along with the oil and supplier companies which had already set up shop in the city, this helped to create an industrial cluster which would attract others in its turn. The outcome was a rapid change from a sleepy small town, which celebrated every time a steadily larger oil tanker was launched at the Rosenberg yard owned by shipping magnate Sigval Bergesen the Younger.

Stavanger now entered a hectic growth period. In 1970, Rosenberg – now part of Kværner-owned Moss Rosenberg Verft – had converted from oil tankers to technically advanced liquefied natural gas (LNG) carriers with spherical tanks. During the late 1970s, this yard made yet another transition to become an offshore fabricator building modules for platforms and assembling whole topsides structures. The Statfjord B topsides in 1978 was its first test, and it continued to produce such facilities throughout the 1980s and into the 1990s.

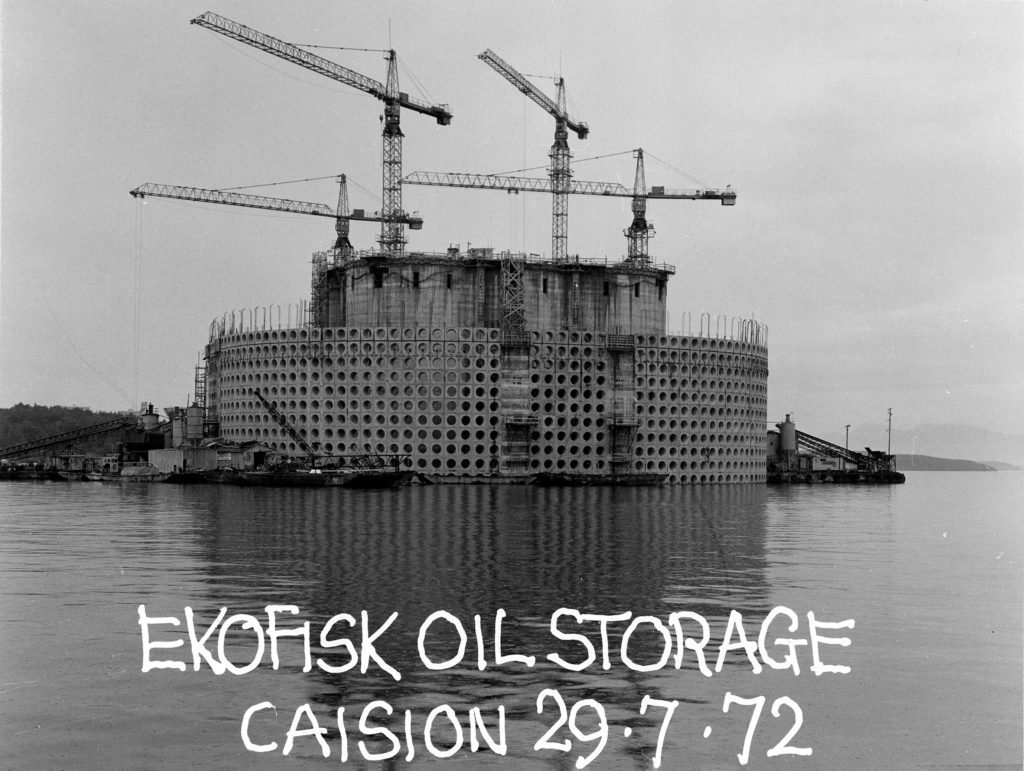

Developments at Rosenberg were closely related to Stavanger’s other “industry adventure” in this period, at Hinnavågen and Jåttåvågen. That was where Norwegian Contractors (NC) built one concrete structure after another, starting with the Ekofisk tank. Intended for intermediate oil storage, this was subsequently converted to a process and control centre on the field. From 1973, NC specialised in the development and construction of its Condeep design. This was based on gravity base structures (GBSs) to carry offshore production facilities.

A total of 16 concrete structures were built in Stavanger to stand on fields in the UK sector as well as on such Norwegian developments as Statfjord, Gullfaks and Troll. The last concrete structure built in the city was the hull for the Heidrun tension-leg platform, a floater installed in the Norwegian Sea in 1995. That marked the end of the road for NC, which was wound up, and the Kværner Rosenberg yard also found itself with less work to do.

Stavanger changed physically through the conversion of former farmland and uncultivated acreage into industrial and base areas serving the oil industry. Dusavik in the city and Risavika in the neighbouring Sola local authority secured quays, workshops and administrative buildings for this purpose. One oil-related company after another set up shop in the Forus development zone, while commercial buildings, hotels and restaurants sprang up in the city centre to give it a new skyline.

oljen forandret stavanger-regionen, engelsk,

oljen forandret stavanger-regionen, engelsk,Shoulder to shoulder

Stavanger’s politicians and business community stood shoulder to shoulder in efforts to facilitate the oil industry. An appropriate terms for the period since 1965 is the politics of unanimity. The emphasis has been on consensus and on reaching common goals. To begin with, such collaboration was promoted by the urgent need to lay the basis for new jobs and housebuilding. Formal processes with oil issues were often characterised by haste because big sums of money were at stake.

The first homes built for US oil explorers at Slåtthaug in 1966 were started in March and completed in June. Construction of the Ekofisk tank began the day it was approved by the council. The same speed marked the Condeep projects. Building up the expanded local authority and the fight to become Norway’s oil centre were both characterised by this sort of collaboration.

The cross-party agreement which prevailed in Stavanger politics was perceived as a strength and an advantage in many disputes. These included the location of Statoil and the NPD, and the long-term plans for establishing the local university. Similar unanimity prevailed over the development of the Forus industrial zone, apart from the emphasis given by the Centre Party to agricultural interests. Active communication also occurred on all these issues between business leaders and central politicians across the Stavanger region. Efficiency and getting things done have been valued almost uncritically in the city. That has proved successful in promoting its commercial interests.

Questions have been raised over whether the ties between key political players in the region and heavyweight commercial interests have been too close. Little opposition has existed, particularly during the long periods of prosperity for both city council and most of the residents.

Economic growth

Stavanger was a relatively poor industrial town in 1965, occupying 18th place among Norway’s urban centres in terms of per capita income. Since then, it has experienced a huge increase in prosperity and has become one of the richest towns in the country. That has given the council the resources to invest in schools, day care nurseries and nursing homes. Nevertheless, overall local provision is no better than the Norwegian average.

The growth in prosperity is perhaps more obvious with regard to private consumption. With high incomes, many residents can afford expensive homes, cars, holiday cabins, boats and travel. But that phenomenon is not confined to Stavanger. Norwegians in general have become “richer” compared with people in other parts of the world.

One of the big challenges in Stavanger has been that oil-related growth has contributed to high levels of pay and costs. As early as the 1970s, other local industries were complaining that big wages in the oil sector left them short of qualified labour. House prices became so high that people on ordinary incomes had problems buying a home – an issue which has not diminished in recent years. Rents and prices for flats and houses are among the highest in the country. Students, young people and workers in low-paid occupations have been losers in the housing market. The flight of jobs to low-cost countries since 2000 has become politically relevant for oil companies which have been complicit in sending costs sky-high.

Norway’s third largest urban region

From being a municipality with clear boundaries, Stavanger has developed into the centre of a metropolitan region while retaining its traditional status as Norway’s fourth largest city. It ranked as that in 1965 with 78 000 residents after a merger with the adjoining Madla and Hetland local authorities, and again in 2015 with 132 000 residents.

According to Statistics Norway, however, Stavanger/Sandnes, including Sola and Randaberg, now qualifies Norway’s third largest urban region. One effect of its oil-related growth is that the city has now merged physically with its neighbouring communities into a metropolitan area of 215 000 residents.

Local government boundaries have been virtually eradicated, with the region viewable as a single residential and labour market – and this expansion has not been without its problems. Major discussions have been held about urban growth versus preserving agricultural land. The many new jobs combined with a decentralised housing structure have clogged traffic, presenting challenges in creating new roads and public transport solutions.

A regional approach, with Stavanger at its centre, has grown stronger at several levels since the 1990s, giving rise to intermunicipal companies to tackle various tasks. These include Lyse Energi, Ivar IKS and Forus Næringspark, which ensure electricity, water supply and industrial sites respectively across council boundaries. The local councils and the chamber of commerce have set up collaborative bodies to develop functionality and innovative thinking. But no overarching political structure for the region has yet been put in place.

In 2020 Stavanger mergered with Finnøy and Rennesøy, not with the twin town Sandnes who wat to be independent from Stavanger.

Cultural flowering

Stavanger’s cultural ambitions expanded as its economic position improved. The local arts festival, for example, was staged for the first time in 1983, repeated in 1985 but killed by the 1986 oil price slump.

oljen forandret stavanger-regionen, engelsk,

oljen forandret stavanger-regionen, engelsk,During the early 1980s, too, cultural institutions such as the theatre, museums and symphony orchestra benefitted from increased sponsorship by oil companies and suppliers.

The city acquired several cultural buildings financed by a mix of public and private funding, such as the concert hall, the cultural centre, the Rogaland Art Museum and the Norwegian Petroleum Museum. Several facilities have been built by the council for both elite and mass-participation sports, with the Viking Stadium, Sørmarka Arena and the DNB Arena as the newest and finest.

The biggest manifestation of Stavanger as a cultural centre was its year as a European City of Culture in 2008. At the end of this period, the foundation stone was laid for a new cultural centre which opened in the autumn of 2012. Funding by the city council, sponsors and central government have laid the basis for a rich cultural life compared with other cities of comparable size.

Population and identity

The attitudes and sense of identity among Stavanger’s residents have undoubtedly changed in many respects during the Oil Age.

oljen forandret stavanger-regionen, engelsk,

oljen forandret stavanger-regionen, engelsk,Founded on the basis of the cathedral, the city has always been known for strong religious attitudes. It was known as the “mission town”, and is the only place in Norway with its own missionary college. Another nickname was “temperance town”, and opposition to consuming alcohol long had strong roots there. This, too, has changed since the oil industry arrived.

The chapel and missionary movements are no longer dominant. Instead, the city centre now offers a high density of restaurants and bars. A striking example is that Betania, the meeting house of 19th century revivalist preacher Lars Oftedal, is now a theatre with an alcohol licence.

People from Stavanger, popularly known as “Siddiser”, earlier had a reputation for being a bit quiet and modest, but have become more assertive and self-confident.

The city’s population has been characterised by immigration since the 19th century, but largely from the surrounding rural areas. Now dialects from all over Norway and many languages from around the world can be heard in its streets,

Internationalisation began earlier in Stavanger than in the rest of Norway because of incoming oil personnel. Well-off Americans, Britons and French people set their stamp on the city, and were followed by immigrants from Pakistan, Vietnam and so on. Just under half the foreign arrivals in the city come from the EU and the European Economic Area, the USA, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. Poles represent the biggest group. The remainder hail from the rest of the world. With about 22 per cent of its population in 2019 from other countries or born to immigrants, Stavanger has become one of Norway’s most diverse cities. Only Oslo and Drammen on the other side of the country have a higher proportion of immigrants. However, a similar tendency can be discerned in Norway as a whole, with residents from abroad accounting for 17.7 per cent of the population on 1 January 2019.